If you’ve ever visited Rome, then you have some familiarity with the sampietrini– the square-shaped (but actually pyramidal) basalt rocks that line some of the more photographed areas of Rome and Vatican City. They are iconic, and have been since they were first laid near Saint Peter’s Square in the 16th century– hence the name, “sampietrini”. At least that’s one version of the story that I’ve been told.

When I was new here and first learning about the sampietrini, I was taught the expression, “E’ una fabbrica di San Pietro.” It’s a Saint Peter’s factory. That’s a pejorative reference to the years and forms of bureaucratic commissions that oversaw long construction of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Reforming the Italian Constitution or any other task that feels like nothing more than an eternal and unfinished work can be a fabbrica di San Pietro.

I’ve been thinking about the sampietrini a lot lately since I’ve been watching in real time the paving over of these black stones in central Rome. For practicality’s sake (I guess) the city is opting to go ahead and replace a number of streets with more modern asphalt which, in theory, should make for a smoother drive. The tradeoff, of course, is that these streets lose a key sense of their identity. And while I won’t paint everyone with the same brush, I’d also offer that those protruding and not always smooth sampietrini did help force some of Rome’s more indiscriminate drivers to slow the F down lest they cause damage to their own vehicle’s undercarriage. Some people in this city will not slow down for pedestrians, but they lay off the gas to protect their property.

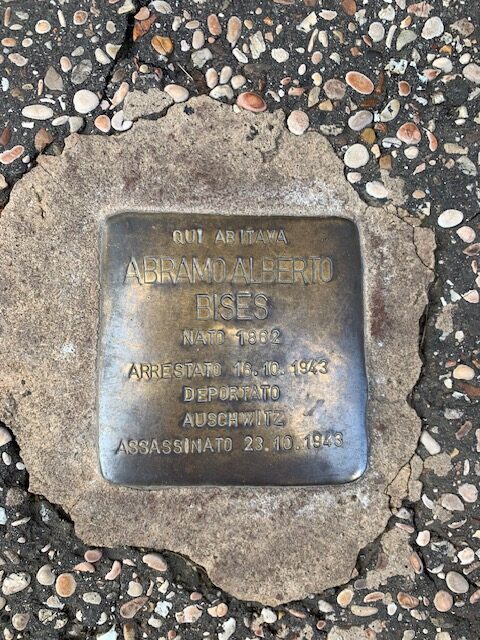

And then there are other touches about the sampietrini that I appreciate. The seamless incorporation of stumbling stones, for example. You find these brass cobblestones throughout the city (and indeed in Europe), and they quietly stop you in your tracks and make you remember that not too many decades ago, people like you and me were taken from their homes and sent off to extermination camps. If that’s not a preservation of a city’s important past, then I don’t know what is. Sure some of the stumbling stones are inlaid into asphalt– but I just don’t think the look is the same. But I’m grateful they’re there in the first place.

Even within Rome, you can still find places that still contain traces of the oldest highways in Europe: the old Appian Way. Most of it is gone, but there are still some strips where you can spot awkwardly large yet smoothed-over stones: ruts worn in where wagons or carriages made their journeys up and down the boot. It’s like sea glass made on land. This juxtaposition between now and then roadways is one to behold, and again I appreciate that small traces remain.

Back home, our part of Cape Cod is known for its pink granite. A few hundred years back, it was quarried and used to build Falmouth’s buildings. Those methods are long gone, but pink granite is still something that is easy to spy when you’re at the beach and walking the rocky shoreline. Growing up, I recall a newspaper clipping on our fridge that contained a black and white photo of a granite gristmill. In the middle was a flame. Had I managed the attention span back then, I would have read beyond my aunt’s pencil penmanship that noted our family’s personal history connected to this gristmill. Or at least that’s how the lore goes.

When President Kennedy was assassinated, his widow Jackie requested that an eternal flame be constructed. Recalling the couple’s love for the pink stones of Falmouth, she reached out to a shop owner on Palmer Ave and asked if he could procure this granite for the gravesite. The story goes that they found pieces in stone walls and areas from Falmouth Village to Woods Hole. Woods Hole is where the newspaper clipping comes into play.

My great grandmother, Annie Broderick grew up in one of the oldest houses in Woods Hole. These days, the Broderick House is owned by the Marine Biological Laboratory– but in my Dad’s time, he would visit Woods Hole since that’s where his mother was born. Next door to Annie’s was Mrs. Tinkham’s house, and she had a pink granite gristmill that was used as a step outside. “We used to play on that step!” is what my Aunt Mary told us when she brought over that news clipping. My father, on the other hand, can’t say for sure that the gristmill surrounding JFK’s eternal flame is that very same one from Woods Hole– but I think the odds are good enough to be true. Either way, the story of Falmouth’s pink granite composing JFK’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery is a true one. It does my heart good to know that the pieces that once built my hometown were selected for such a noble purpose.

It’s kind of ridiculous to draw a comparison between the iconic cobblestones of Rome and a bit of my town’s contribution to our national history. But I do think of both as an example of how, over time, we’ve quarried for various sources that were once of great use, and are now largely an emblem for how things were for a period of time. The Saint Peter’s factory concept is not just for bureaucracy– but it can also apply to how we’re constantly building and rebuilding our world. Paving our lives and then repaving them again when that foundation is no longer suitable. Is this effort always in the service of good? Probably. Does this upgrade come with a sacrifice of aesthetic details that make one place unique? Of course.

I will say that in Rome, it is very easy to walk around and spy the edges of asphalt streets that still have a border containing sampietrini. It’s all part of the layer cake that is Rome. The same with Falmouth. Once you know what you’re looking for, you can find pieces of pink granite in cornerstones anchoring homes, buildings and indeed stone walls. Progress and eternal labor are both fundamental to how we live– I’m just glad that we can save vestiges of what was once so we can always judge how far we’ve come along in the effort.