What does it all mean? What is it all worth? How does one move forward when the operating boundaries are suddenly redrawn?

These are questions I think about when one day you wake up and a peak on the Belledonne mountain range is suddenly gone. What was once an accepted presence—and as such a part of life’s rules—is suddenly absent from the performing cast. When someone dies, in the eyes of a community, there’s an experience of double loss. On a realistic level, you grasp that this departure is a part of life’s circle…but on a painfully personal and selfish level, a more profound mourning takes hold.

I turn these questions about meaning over in my head, slowly as if clumsily flipping a 5-franc coin between my fingers. It’s more of a meditation than a hunt for truth. This is because I’m 43 years old and the already accepted reality is that I just don’t fucking know.

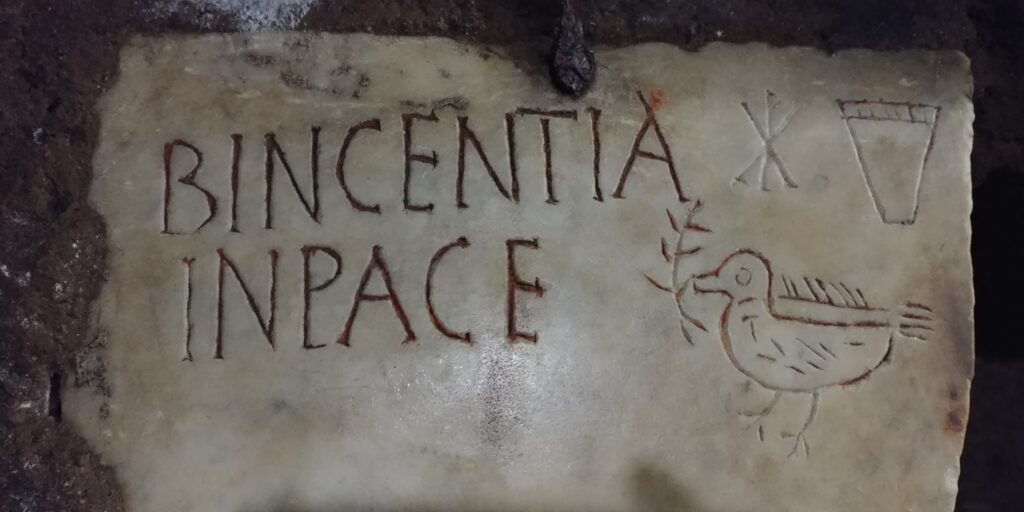

On Sunday I visited the Catacombs of San Sebastiano—a large network of resting places that was used starting in the 3rdcentury. The basilica on the surface holds the Sebastiano’s relics: one is an arrow reputed to have killed him the first time, the other is a pillar upon which he was tied and killed again. Over time Saint Sebastiano was seen to intercede and protect people from the plague….a plague judged to be historic. Some intangible event never to be repeated again.

Whether you believe all of Sebastiano’s tale or none of it at all, you can’t get around the truth that the story of one person’s life has held significance for many people. The ripple effect has lasted centuries. His presence mattered.

Plague or not, it’s hard being born into this world. You’re hauled on out and you start moving through the wickets before you even realize what’s going on. And once you’re aware of the “adversity-achievement-great more adversity” pattern, that’s when you see that life has more unknowns than certainties. Sometimes the excess of unknowns is enough to make you want to disregard the incoming obstacles…except that life is a moving walkway and you pretty much have to keep on going.

So as a fellow human on the walkway of drudgery, it makes a real difference when my routine-heavy existence is injected with joyful touchstones. People of positive effect. Especially when it is least expected—but probably when it is needed the most. More than others, these sources of light play a powerful role in boosting others with a sense of reassurance.

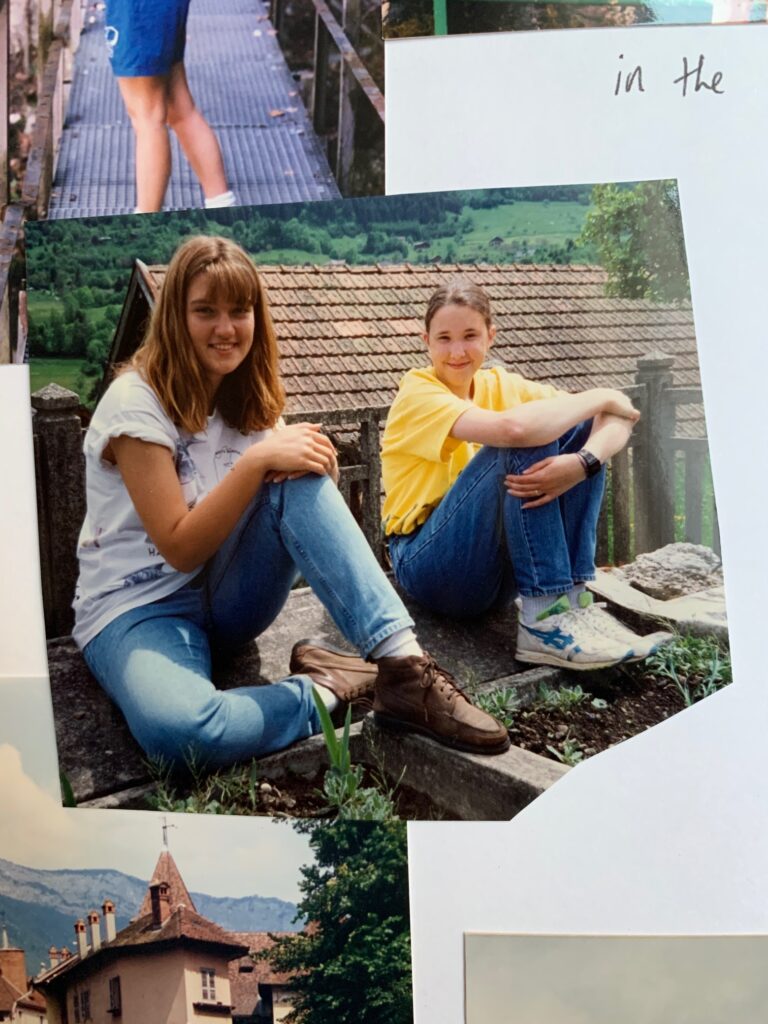

You rarely realize it at the time, but such rencontres ultimately translate into something significant. For me, I recall life as a 16-year-old who had just gone abroad but was ill-prepared to deal with it all. I didn’t click with the French families assigned to host me during that year, and this could have spurred a lifelong reluctance de faire un pas hors de ma zone de confort. To never again go outside of my comfort zone. But it didn’t. And there’s an important reason for that.

Maybe it was through sheer luck or perhaps a bit of divine intervention, but I found refuge and acceptance with two special families who were hosting other American students. One family in particular has been weighing heavily on my mind for the past couple of weeks. I am thinking about them again right now.

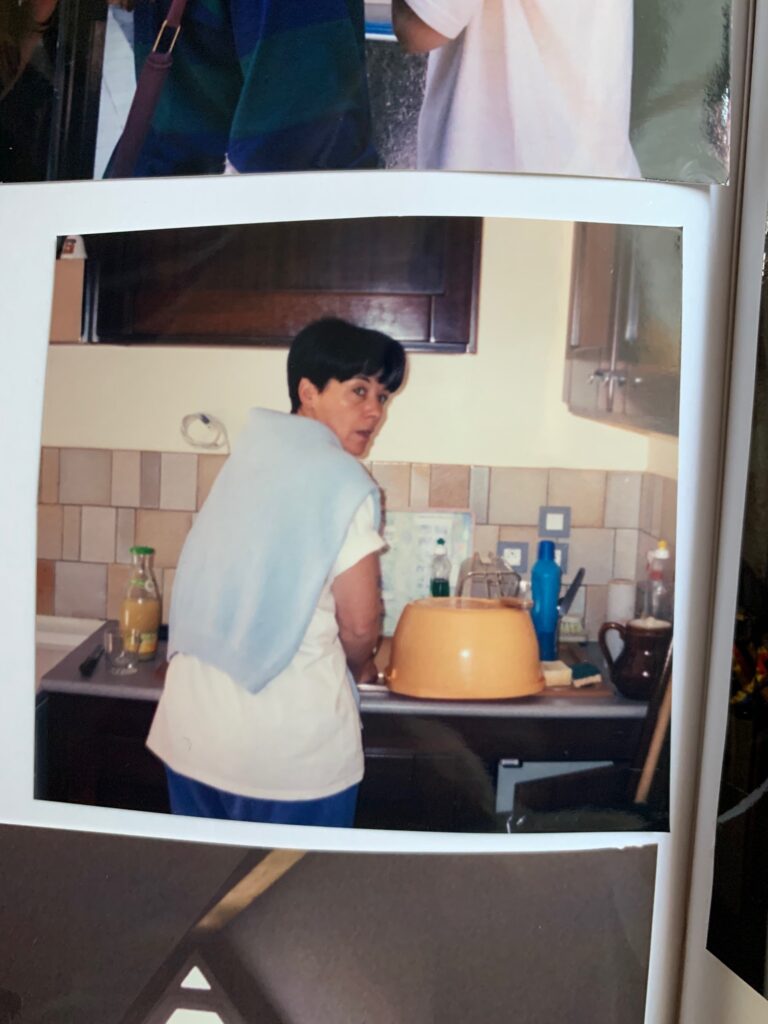

I remember one of the first times I stepped foot inside that family’s Meylan home. As a shy kid with shitty language skills, I steeled myself for an interaction with “les parents”. My new American friend invited me over, telling me about how wonderful Maman and Papa were. I’d already met their son in the common area of the lycée. He was tall, handsome, and had these eyes and a bright smile that beamed across the room. It would only be a matter of time where I would discover where his brightness came from.

If I ask you to imagine a typical Frenchman, I wonder what you might think. If you’re an American who has never wandered beyond the backyard, perhaps you see some guy with a permanent sourpuss who spends most of his time giving judgmental shrugs to the world. If this is what you are thinking, then you need a few more touchstones in your life. You need to visit a place like Meylan, St. Mury, or La Buisse. It will make your life immeasurably better.

The French parents whom I met that day became touchstones for me. Especially the papa. A force for good all his own, he was the guy with a big smile who could put you at ease without even knowing that he was doing it. Language barrier or not, that dinner table was always set with unconditional kindness and plenty of laughter—and as a very sensitive teenager, I desperately needed that. As a human being, I still need exactly those things in order to get through the day.

To say that this Papa has now been relegated to the larger tally of pandemic deaths—to me this feels both senseless and ridiculous. Almost unacceptable. Because while I accept that we will all one day die, this doesn’t even begin to tell a fraction of his story. I might never have been personally touched by the dust of lives that accumulate in a Roman catacomb, but I can personally vouch that one man’s time on this planet has been meaningful for people far beyond the Grésivaudan valley.

When bright and shining personalities leave this Earth, the clutches of people who have grown accustomed to their glow feel boundless, indescribable sadness. Pas de mots. It’s because they can never be adequately replaced. And if these bright lights are snuffed out at the hands of a global pandemic—one that is ripping so many other wonderful lives away—this somehow makes it feel even worse. The existential questions become even more burning. But there are still no answers.

I’ve really got nothing else to say. The pandemic continues, and as humans we can only do so much until this becomes another sterile entry in the annals of history. We will go on, because we have to go on. Life is still out there for us to navigate, and in doing so, the best that we can do is remember how we have been formed up until this point. We remember the goodness of those who stopped for a moment while on their own path. Who thought nothing of making us smile, and remembering that while there are many uncertainties out there, it is ultimately okay. Now and in what we will leave behind.