When you’re going through some kind of life transition, standing at the foot of whatever you are tackling is always the worst part. And further, life is relative—so what might look pretty intimidating to you may seem miniscule when compared to the situation of someone going through something worse. This type of comparison, much like the calm before a sizeable To Do situation, has a tendency to sprout unproductive thinking. You’re almost better off not thinking about either at all.

If only.

Of course, everything feels tough until you set off into the woods and just get on with it. Strangely, it is only when you start to negotiate the thicket that you realize that everything is actually navigable.

And I’m not saying this because I have suddenly gained complete mastery for tasks involving complex movements. Never. it’s more that I am just remembering that there is nothing like diving into a problem (or being pushed) in order to find focus. Concentrate on what’s only directly in front of you: the big tree root in front of your foot presenting a trip hazard if you don’t pick up your foot in the next split second. Or the big mover’s truck that has just shown up at your building and is asking where they are able to park. You have always known that there is no legal place to park the truck—but now you must lift up your foot and find a solution. And if you don’t, then you’re going to make all of the follow-on subtasks infinitely harder. Those that comprise leaving the country with minimal trace and administrative pain.

Back to everything being relative—I do recognize that packing up and moving is not some sort of hero’s journey. It’s more like ensuring that you get your life just enough organized to be pushed out of your current situation and into a wormhole where you and your stuff eventually crash-land elsewhere. Once you’re back on the ground, you get up, have a look around, and start to get your bearings again. And then you rebuild again from there, using the resources that are the result of silent hands that have been helping you along the way.

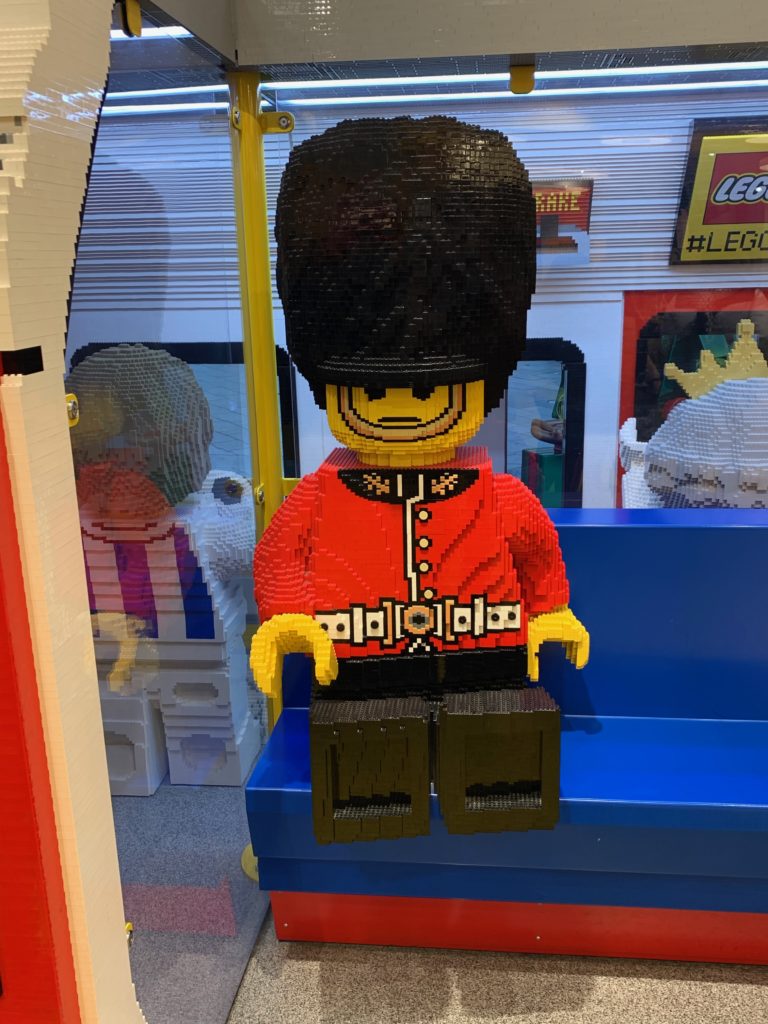

I own an annual planner that serves as a more permanent companion to what I write on the back of my hand. It is filled with trips and tasks that I must do throughout the entire year—everything from the boring dental exam to the more taxing change of duty station. The bigger things, I find great difficulty in wrapping my brain around them when they’re scrawled as an all-encompassing entry. Back in January 2019, when I first wrote “Leave London”, I did it with only a passing thought. Yeah Yeah. Somehow that whole thing is going to happen.

After carving out a life of specialized routines for the past 4 years, I knew that such a transition would necessitate a lot of stops and starts. Like disconnecting my internet connection while knowing that at some time and place in the future it would eventually be plugged back in again. But the act of getting all of these tiny details accomplished: the bill payments, the bank accounts, the goodbyes—my god, the goodbyes—these are all the like free prizes that you used to find inside of cereal boxes. Like those, the quality of each discovery is unreliable and rather scattered across an unscientifically-distributed scale. You just have to open each box up and see how each makes you feel.

I think there’s a reason why adult cereals never had free prizes to begin with. Living the life of a consumer, a mover, and a woods wanderer is really the prize in itself. Even if moving through the shadows and spiderwebs doesn’t always fit the definition of wonderful. But going through these kinds of underwhelming revelations are the very moments that signal we have become adults. And no matter how they make you feel, they are all accomplishable. Once you get going.

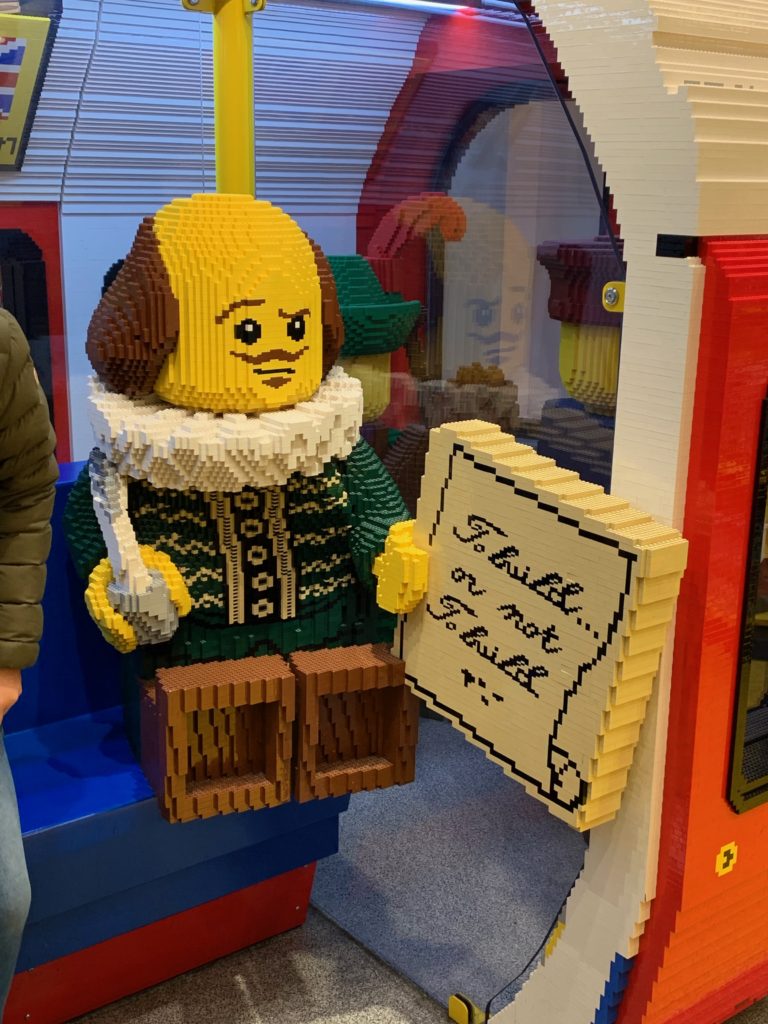

The forest looming ahead, whether it takes the form of an entry in a planner or involves something a bit more life-swallowing, can feel like the most daunting thing in the world. But the reality in understanding that this is only option means that it is simply a matter of walking into it. Find a way to put your brain on standby. And then, if you are like me, proceed to wander in circles a few hundred times before I feel as though I am really getting somewhere. And in gaining this sort of focus, sooner rather than later, the moving truck is packed up and on its way. I find myself walking into a clearing that oddly resembles the doors of Heathrow Airport.

I have a highly entertaining 7-year-old nephew. I enjoy hanging out with him, and when we decide on an activity I like to ask, “Ready for an adventure?” He always responds with an emphatic “Yup!” that is underscored by a single firm head nod. Then, as we set off on whatever it is we will do, he calls out, “Mommy, we’re going on an ad-ven-ture!” There is no hint of expectation or trepidation in his voice—he is just in it for the present moment.

It sounds a bit nuts, but there’s a part of me that always thinks of him—or better yet his unself-conscious attitude—when I find myself coming upon moments of adulthood flux. Especially if I don’t know exactly where I’m going, or what I might encounter. Like him, at some basic level, I should just wander in and accept that all I know is what I know: that it will be an adventure, and I’m already going. The rest, as is always the case, will sort itself out.