My introduction to Kazuo Ishiguro came in a literature class that I took during my year at UMass Amherst. The assigned book was A Pale View of Hills, and it was a story that was deceptively slick with revelations and double meanings that seemed to register only after you’ve been sufficiently jabbed by his pen. I loved the book, and it remains in a pile of selections that has traveled with me from place to place over the past twenty years.

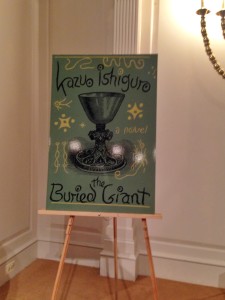

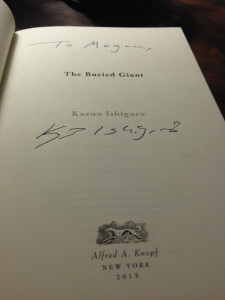

Ishiguro came to Washington, DC this weekend on a tour for his new book, The Buried Giant. When Politics and Prose, teamed up with 6th & I, announced that they would be hosting him, I eagerly snapped up a ticket. Ishiguro’s last book, Never Let Me Go, came out in 2005, so this is kind of big deal that something new has hit the presses.

This entry is not a review of his new book (you can take Ishiguro’s advice and read Neil Gaiman’s review located here). Instead, I wanted to transcribe some notes that I scribbled down over the course of the 45-minute discussion he had with Alan Cheuse. The topics ranged from how he constructed his new book, to a broader and more compelling scope about his craft, and what he fundamentally cares about with respect to the human experience. Please note that any potential mischaracterizations are not intentional, and are likely a result of my flawed penmanship and memory:

75 minutes before the start of the event. He’s worth the wait…and besides, we’re readers. We’ve got something to page through while passing the time.

Q: What is your approach when writing a book?

Ishiguro starts with a premise, or kernel of an idea. He likes to be able to articulate in two or three simple sentences what the story is about. Emotion or energy must come off of these lines. The language and prose comes later.

Q: What was the kernel you had for The Buried Giant?

He didn’t completely remember, but it went something like this: for some reason everybody is suffering from selective amnesia—which stems from a mist that covers the land. There is a married couple who has to decide whether they want their memories back- but they start to worry that they will have remember the bad ones too. This is intertwined with a second story: in their land there are two tribes coexisting, and if the memories return, there is a fear that this peace will be destroyed.

Q: How did this idea of a “mist” emerge?

He made the decision not to create another high-tech dystopian setting as he did with Never Let Me Go. This book draws from historical events: the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the events in Rwanda, and South Africa. He looked at places that have dealt with a divide between two peoples and asked, when is it better to look at things that happened—or keep them suppressed? Real life situations are the prompt—but he shies away from creating a true historical setting because he claims that sticking to the facts is not his forté.

Q: How did you conduct research for Remains of the Day (for the butler, in this case)?

He did two kinds of research. The first involved “nonfiction” research that included postwar European foreign policy and accounts of people working in service. The other research was centered on his work as a novelist. He had to get to know the fictional world he was creating and its atomospheres. It is comedic? Tragic? This is very difficult to do and it takes a lot of time to “research” the imagined world. Reading can trigger ideas but it’s his imagination that is the most important aspect. Once this is established, the prose follows.

Audience Q&A:

Q: What writers have influenced you most?

Before he became a writer, he was very influenced by Charlotte Brontë. Some people are surprised when he says that, and he is too. “I’ve ripped a hell of a lot off of Jane Eyre” he says—how he uses the first person, how the narrator confides in the reader, etc. After his first novel, Proust became a source of inspiration. “Some [writers] influence me who I don’t particularly like.” He finds Proust insufferable, snobbish and boring…but at times also sublime. Writing through memory is a trademark of Ishiguro’s. With Proust he saw how a memory from long ago can be pasted alongside one from the present like a collage. In this respect it makes him similar to an abstract painter.

Q: In Never Let Me Go you touch on the idea of emotional escape from one’s inevitable demise. Why not give the characters the idea of physical escape as well?

Ishiguro finds this an awkward question, and he gets this question the most when he visits the United States (about half of the time he gets asked this in the UK, and never when he is in Japan—perhaps this says something about the American spirit, he wondered). Whatever the case, he said that he needed to create a situation where young people went through the aging process like an old person. He wanted to show the reader something over familiar; the story is about the fact that you cannot escape mortality. Life is short. What other things become important when you are facing death? Declaring love, forgiving an old friend, making things right…all these things become paramount.

No matter how much you love another, you cannot escape your fate, and to create the world as he did makes this the more interesting point. Filmmakers often create the opposite situation, but people do not run away. They stay in bad circumstances, bad marriages, they run into enemy gunfire. People on the whole accept their life and they’ll live it with dignity, to the best of their ability. Movies do the opposite most of the time—but the opposite is the reality. The story is more profound and interesting if we internalize our fate.

Q: How upset do you get when you are writing and your characters go off on a different direction than you expected?

He tries not to let characters do that. When other writers say, “I wanted Harry to do such and such but he wouldn’t let me,” he finds that sentimental. With his approach to characters, he had a “eureka” moment: stop worrying about giving them back stories, making them colorful and worry about the relationships in a novel. Are the relationships between characters cliché? Is it a three-dimensional relationship that can surprise convincingly—with a beginning, middle and end? If he can create an arc, the characters take care of themselves. He notes that perhaps this approach might only work for him—he has read other books with colorful characters that aren’t necessarily connected.

Q: On the subject of cultural and linguistic style, does he feel that he writes somehow in English as a second language? [Drawing from his heritage] Is he able to enter into two societies as he writes?

Ishiguro pointed out that he is illiterate in Japanese and does not see it as his first language. He spoke only Japanese until he was five, but can’t hold an intelligent conversation with a Japanese stranger. He points out that writers like Samuel Beckett deliberately wrote in another language as a way of artistic discipline. Ishiguro was educated entirely in the English language, and from the ages of 5 to 15 he lived in Britain with his family thinking that they would be returning to Japan the following year (his father was a scientist). They never adopted the idea that they were immigrants—only visitors. Accordingly he looked at Britain through the optic of a visitor in the land thinking, “That’s how this nation behaves.” It was not applicable to him but he respected it.

He is careful to mention that while he enjoys a slight distance from the culture, he shouldn’t overclaim some kind of special perspective. That’s too much. He’s immersed and has to struggle as much as everyone else to get a handle on his culture and country (Britain).

Q: On the topic of universal conflict and setting, in the course of your writing do you aim to arrive at the conclusion with a pre-formed answer or do you write and then come upon it?

He doesn’t feel as though he comes to any solutions or conclusions in his work. He’s not even sure that he’s actively looking for a solution to the tension that he creates. Rather, he thinks he’s trying to modestly aim to share emotion with his readers. To just present a certain perspective. “If I share emotion with my readers—just present a certain perspective—if I put it this way, do you share these emotions as well?” he asks. He’s not trying to offer practical solutions. He thinks there is value in this approach, and books, music, and movies all do this. We’re all human beings, and there are not hard truths.