“What do you think is better? Restoring what has been damaged or leaving it as it stands now?”

This question came about after a series of low-grade exposure to vestiges of the past. These usual take the form of a small placard placed in a static display amongst immaculate or revered places of our world. They are modest and easily overlooked—but they offer a window into a drastically different era this is not our own.

The European continent isn’t the only place that serves as a sort of “we’re open for business—just don’t mind all of the dead” boardgame of the past. This is the of course the case for the entire planet. I say this because on the whole we humans, in my opinion, seem to excel in destroying the beautiful things that we also spent years building. Creation and destruction and recreation. I recognize that this it’s pessimistic to frame the world in these terms, but it’s kind of hard to ignore when there’s a little steam shovel outside of my house right now digging up the entire sidewalk.

But before I allow my thoughts to grow so large that I can’t warp my arms around them, I’ll return to the original question. Concrete questions, after all, seem easier to tackle and, in the end, provide me with something that I can both easily digest and apply in practical terms.

Would I want something to be restored—or at best retouched in the image of how it first was? My immediate reaction is “Maybe not”—the news is rife with hilarious yet tragic stories of art retouching gone awry. For certain, this is not the kind of restoration that anyone would want to risk.

On the other hand, almost all of the old treasures of the world remain and are magnificent largely thanks to the work of many capable hands. I find it hard to believe that Ecce Mono isn’t an exception to the rule. And while humanity’s painstaking efforts to keep the past close to us here in the present day, I don’t feel completely on board with blanket restoration work.

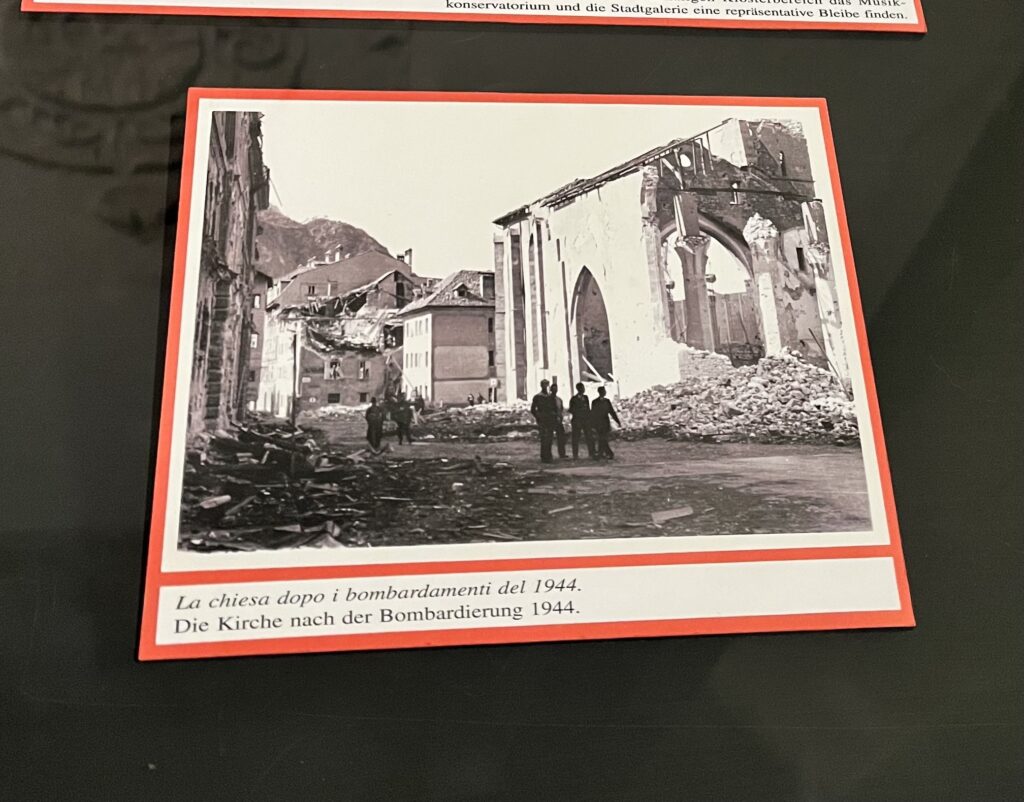

I think about this café that I recently visited for breakfast. The entire place gleamed with sharp, off-white walls that were contrasted by clean, dark-paneled wooden cabinets and coffee bar. It is possible that they just replaced the décor, but the out front says “Since 1947”. As I sat at my little round table and drank a cappuccino, my eyes fell upon a small strip of wall next to the espresso machine. Mounted in one frame were two little black and white photos stacked one atop the other. They were, of course, depictions of the building taken at the end of the Second World War.

It doesn’t take a military historian to guess that the town, situated at a strategically significant exchange point, was one of many prime locations for targeting. The photos on the wall reveal a tall edifice that looks as though the façade had been the victim of a large and powerful swipe down the front, leaving the skeleton of the inner floors exposed. All these years later, through rehabilitation and reinvention, folks like me now sat in relative ignorance for how this place once was less than a hundred years ago. Or we’d be ignorant if not for those two photos.

There are plenty of other places like this one in the world. Places that bear scars both hidden and exposed. Partially, completely or not at all repaired. The Palatine Chapel in the Reggia di Caserta- damaged by American bombers in August 1943—was restored to its former glory except for a but a few columns. The General Post Office in Dublin which, if you stand out front and look up, you know that only the front façade remains following the 1916 Easter Rising when the rest of the building caught fire. Echoes of history are all around us, and especially these ghosts remind us of the violence that once (for most of us) as we now occupy a rather mundane space of movement. Again at least for most of us.

Being able to ponder a society’s visible scars when they’re juxtaposed with follow-on efforts to recapture what once was is a pretty moving experience. It reminds us of the wide swath of complementary and conflicting possibilities that we are capable of as humans. And with these thoughts in mind, I had my answer to the original question. If it’s at all possible and of course, practical, I prefer to bear witness to a hybrid of past with present.

* * *

This past weekend I was watching a rendition of the old Stevie Wonder song, “Someday at Christmas”. It is one of my favorite Christmas songs—but this was the first time that I’d heard an updated version. It was Lizzo performing on Saturday Night Live and I smiled after noticing that she’d made a slight modification to the lyrics.

The usual ones are:

Someday all our dreams will come to be

Someday in a world where men are free

Maybe not in time for you and me

But someday at Christmastime

Instead she sang:

Someday our dreams will come to be

Someday in a world where we are free

Maybe just in time for you and me

Someday at Christmastime

Maybe just in time for you and me. It’s a 180° change from the usual “maybe not in time for you and me”, and it’s not immediately noticeable if you don’t know the lyrics. But it’s a significant perspective shift. The song already has a bit of a down note as it opens with “Someday at Christmas/men won’t be boys/Playing with bombs like kids play with toys”. The adult truth of life, even at Christmas, is that we might not get to a place where we hope to be. But maybe we will. And we will see things that we might not have gotten to see. This whole creation-destruction-recreation bit is on a constant loop. We’re just here for some part of it.

Maybe just in time for you and me does offer us a shot at occupying space on the other side of the coin. Maybe in our lifetime we will be in a spot where we can enjoy our surroundings and have enough space to properly study what came in the past. Marvel at how we’ve (hopefully) evolved, and how society has grown a new bit of skin over the wounds that could not be avoided. Never perfectly healed, but enough so that you remember what once was and what now is. That’s where I want to be: Just in time for us to see.

I recognize that not much of this ranks very highly on the festivity scale. Indeed, I’ve been thinking a lot about closing this entire site down come the end of the year. I’m not sure if I’ll do it, but I think a lot about the lifespan of things: how they grow, die away, and then come back again in another form. All of it is okay—and to me it’s the witnessing and then remembering that is the most worthwhile. It keeps us hopeful, and reminds us that plenty of goodness is going on somewhere within our lifetime. And hopefully this will continue to be the case for others as well.