On any normal non-pandemic day, a hospital has no shortages of seemingly ridiculous aspects: The dressing gowns we are handed that are hardly fastened by string ties, The shower curtains that divide you from another patient while each of you divulge private details of you body that you would hardly divulge to your next door neighbor. The tiny gift shop offering suddenly priceless trinkets of comfort that are a far cry from anything you would ever normally purchase for a loved one.

But here in these Years of Our Pandemic, the requirement to visit this one particular hospital feels even more ridiculous. It’s a rather large and well-known place that caters to a capital city population. Sitting up against a major motorway and right next to two other intersecting motorways, the real estate is eaten up by sound barrier walls and access roads that leave no room for adequate parking. I am unsure of which came first— the roads or this mecca for hopeful recovery— but I can tell you that there is a ridiculous lack of parking and public transportation options.

When the parking supply does exhaust itself as it always does at the post-sunrise hour, patients (and presumably staff) are left to their creative devices. It is generally accepted that the next best option is pulling to the side of a busy overpass that is walled upwards on both sides by a box-shaped chain link fence. For me this entire configuration is reminiscent of the overpass connecting Kenmore Square to Fenway Park: at peak hour it’s abuzz with humans and vehicles while even faster cars buzz below you on the Mass Turnpike.

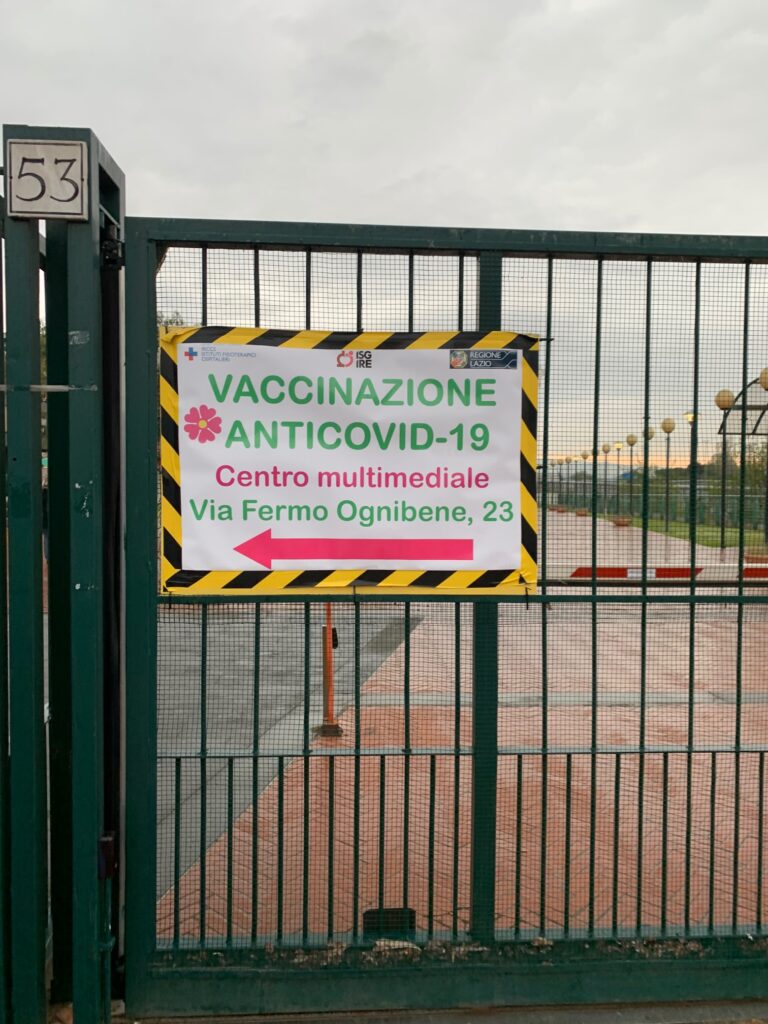

Due to COVID-19, a sponsor, helper or person not requiring medical attention is barred from joining the snaking and socially-distanced queue leading to the hospital’s entrance. The line is manned by a nurse who hands out forms and quizzes each person as they wait. Some modern day version of Charon. The line is long, and if the sun were shining and the lingua franca was different, these people could perhaps be waiting to be scanned in at Gate C of Landsdowne Street. Except all of them are soberly breathing behind face masks, they are clutching hospital paperwork sheathed in plastic folders. None o f them are clad in red, blue or white Boston gear. Instead, the only uniforms to be made come with the varying styles of face masks juxtaposed against the medical staff team who sport buttons on their coats that say, “Io mi sono vaccinato” I got myself vaccinated.

Half of the people who come to this place get to enter in order to be seen for whatever is wrong. The remainder who come for moral support and are in good health (at least on this day) must return to their cars. It’s the only place where you can remove your mask and breathe without anxiety— plus it’s also raining and the patterns of vehicular traffic do not encourage leisurely strolling.

From the safety of a car illegally parked on a highway overpass, it is possible to watch the rushing of others with similar agendas. The shoehorning of Smart cars backing into impossible parking spaces, the emergence of elderly couples as they carefully walk against traffic on the asphalt rather than circling back to favor the footbridge. Nearly all of the women in advanced age have hair that is dyed the color of What Must Have Been from twenty-plus years ago. The false hair color does nothing to cancel out the aging effect that a medical face mask has, and I make a mental note to one day stop dying my own hair. At some indeterminate point in time, you’re not fooling anybody except yourself.

And speaking of fooling oneself, even with surgical masks blotting out at least half of a person’s face, through eye gestures and body language it is simple to recognize that almost everyone is ill at ease in crossing the overpass and turning to join the queue of the sick. Sure hospitals offer just as much hope as they do finality, but it’s far too easy to linger on the more foreboding aspects of this place. Especially when it is situated far too closely to the fastest motorway taking you away from the country’s nerve center. And again nobody can be surprised; it’s not like we all won’t someday enter one of these places on foot and then re-emerge under a means that is completely not our own.

Reminds me of a time as a kid when I rode in the back of my aunt’s blue Ford Escort as she drove with the seatbelt clipped behind her chair (as she always did) and brought her elderly mother to the hospital. “I don’t want to go,” was all my grandmother said once we arrived. I remember my aunt, a nurse, giving a stoically dismissive response as they went inside and I waited in the car. It was the last time I saw my grandmother alive and even then I kind of knew it would be the case. The next time I saw her, she was silent and recumbent with a rosary wrapped around her intertwined hands. Looking back now— I’m only half as young as she was at that time— I believe on that morning she had stopped fooling herself too.

In the clinical light of day and reason, of course hospitals and the routines of the people inside are not ridiculous. Everything except the parking is developed from necessity. We’re all built to move about, break down and then eventually be forced to move on to something else. But the issue is that we are humans and are thus equipped with additional features like feelings and an unending thirst to reconcile all of these logistical requirements with emotions and overly-analytical brainpower. It’s no small task…and on many days it doesn’t really jibe to an acceptable effect. So you just straddle the overpass and wait patiently in your car as trucks whip past too closely. You trust with blind faith that your person inside the hospital will re-emerge once again and flash you a detectable smile of reassurance from behind their ridiculously important face mask.