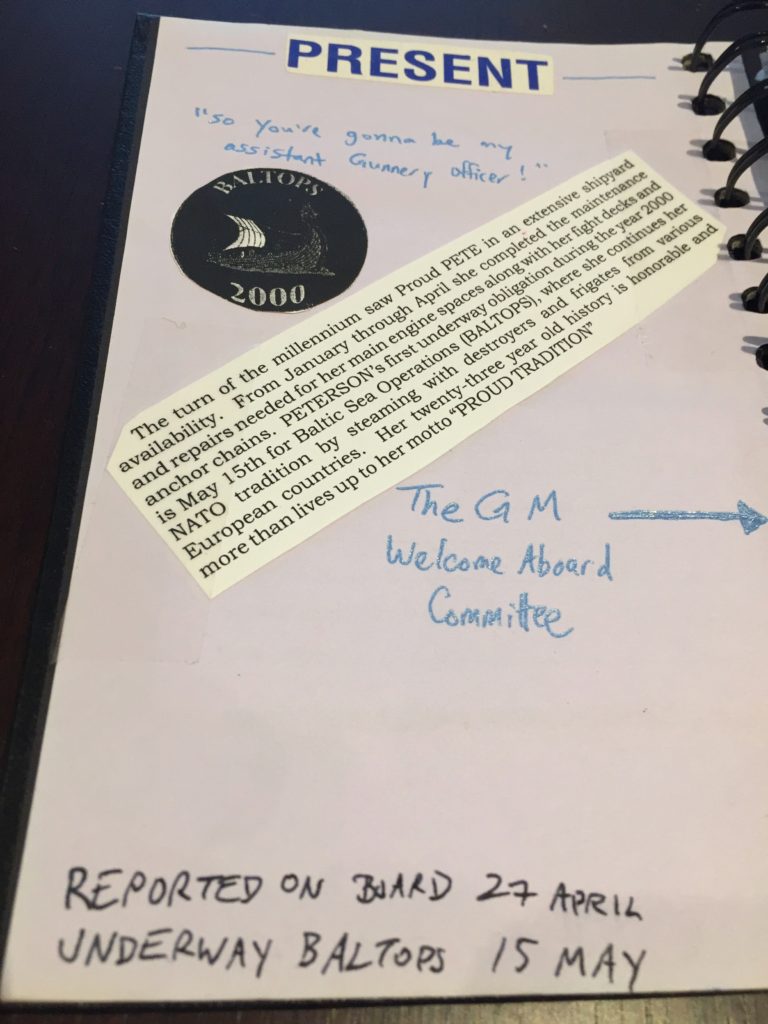

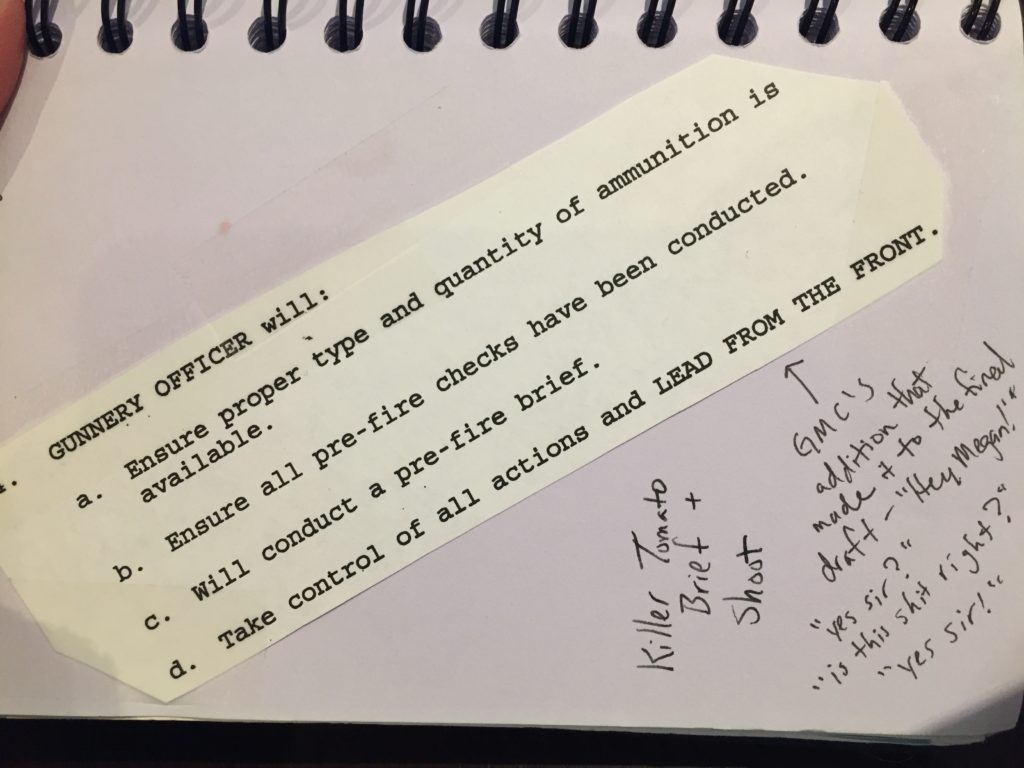

In June 2000, I was a few months into navy life as an Assistant Gunnery Officer when my ship visited Stockholm.

As a newly commissioned officer, my preoccupations included suffering a boyish OCS haircut and learning as much as I could about the Spruance-class destroyer to which I was assigned. My life up until then had been riddled with confident suspicion that I was a slow-learning ugly duckling—so neither the hair nor the knowledge were sprouting as quickly as I wanted. In those days, bits of wild tress stuck out awkwardly from beneath my ship’s company ballcap. It was just one of the many reasons that made my existence amongst the crew feel even more visible.

But on the morning of our approach into Sweden, my hair was firmly controlled under a well screwed-on bucket cover. The headgear was a mandatory component of the prescribed uniform for entering port: summer whites. But we hadn’t arrived yet. There was one major combined evolution still to accomplish before the anchor was dropped: the navigation and special sea and anchor detail. For me it would double as an experience that would prove to be my first big test in the Navy. A chance to demonstrate that I had some proficiency in this complicated new career field.

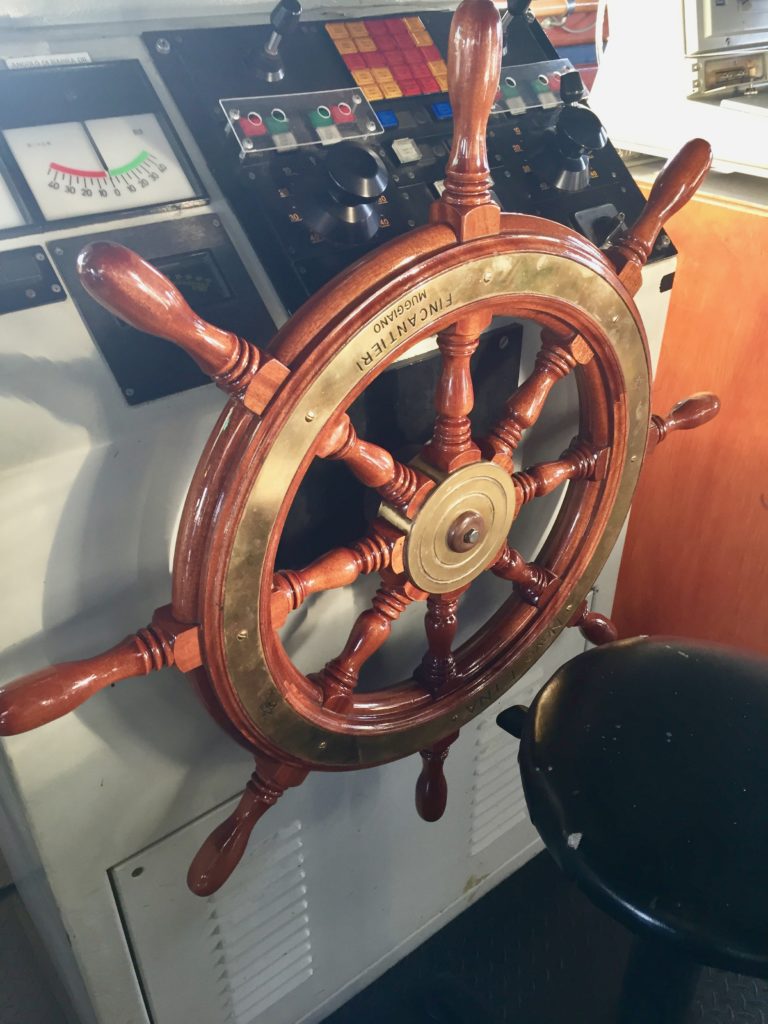

The navigation detail into Stockholm is long—a good 5 hours. This is due to the archipelagic swash that makes up the country’s sea border. My station for the detail was Conning Officer, a job reserved for sailors just starting to qualify as Officer of the Deck Underway. As Con you are a glorified parrot—you spend much of the time repeating standard engine and rudder commands as dictated by the Officer of the Deck. Still, despite the overly-simplified job description, the Con is important because his or her voice is the only one that the helmsman will heed. This is for reasons of both safety and clarity; a bridge gets messy real fast when things start to get interesting.

On that day in the Baltic, I remember the calm sea state as I tried to enjoy breakfast just ahead of the big morning. Smoothing my polyester shirt into the US Navy’s most ill-fitting trousers, I carefully made my way to the Combat Information Center—trying desperately not to brush against any of the endless metallic staining opportunities running the length of the ship. After speaking to the CIC Watch Officer, I headed for the hatch at the center of the space and then moved up the last few stairs leading to the bridge. I squinted my eyes when I reached the top.

On this morning of entering port, the bridge was bubbling with activity but each sailor tended to his or her task in subdued tones. No one wants to get yelled at for being too loud or too lax while the ship is operating in constricted waters. My constitution matched that of the bridge as I attempted to project an air of coolness that belied a dozen SWO gremlins as they bounced around in my stomach. I was 22 years old.

My eyes adjusted quickly to the daylight. Now seeing clearly beyond the bow, I was a bit shocked to see how close we’d suddenly moved towards shore. In the ensuing years, this sense of surprise would never leave me—I’d always find the reality of land jarring after spending extended periods of time at sea. Standing now near the tiny bridge windows, I chatted with the offgoing Conning Officer as he gave me the standard status of operations: course, speed, pilot pickup point, and all the other contacts nearby that we should try not to crash hit. I jammed all of the information into my head. The VHF radio perched just in front of us chattered away in intervals on channel 16 . After completing my turnover, I settled into an appropriate spot near the binnacle.

I’d first obtained familiarity with these new surroundings during the Nav Brief held the evening before. The Navigator reviewed the tracks plotted on the charts track with me before the meeting so I could brief the entire watch team with some illusion of confidence. I must have briefed 50 course changes to the Captain and fellow watch standers—although in retrospect it was probably far less than that. Now as I stood on the bridge in my brand new Bates, I’d forgotten every leg that I had briefed the night before. All I knew was that we’d Pac-Man our way through twisting inland waters for a very long time before finally anchoring in Stockholm.

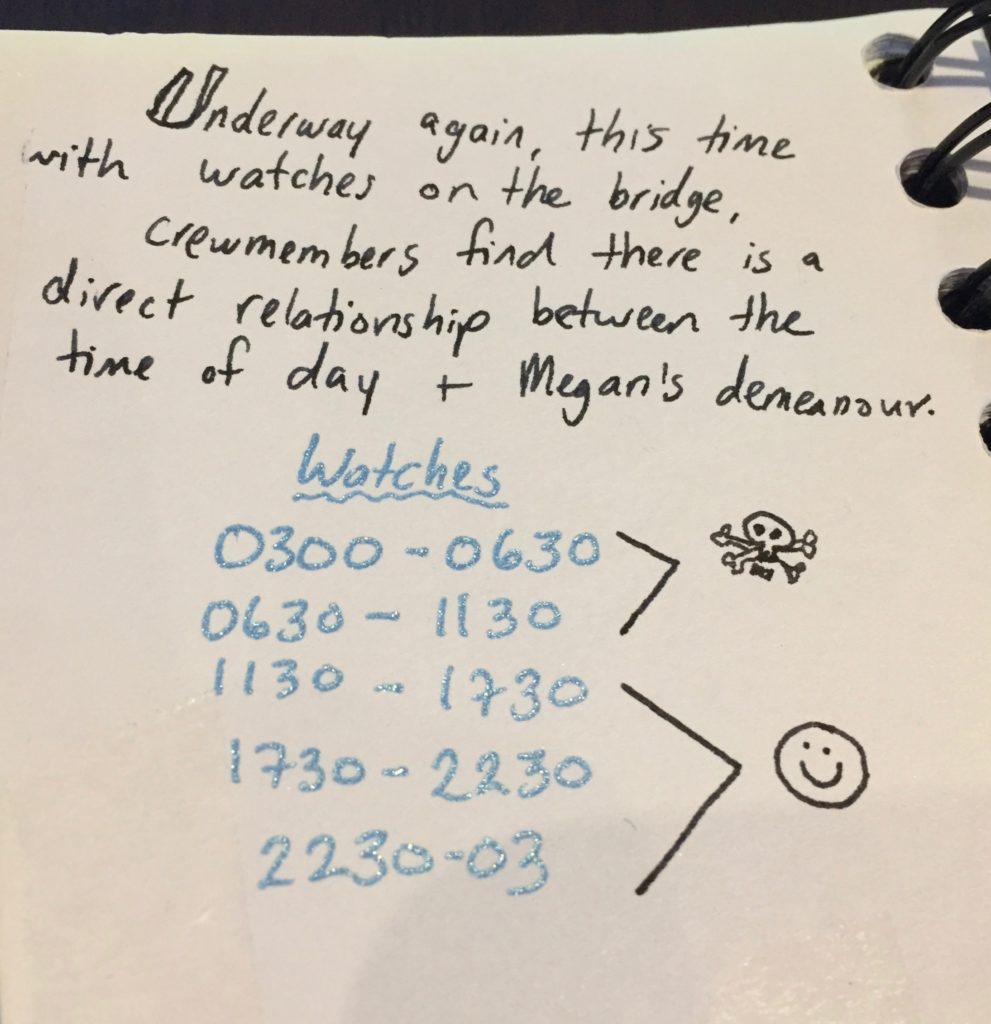

The transition was hard at first, but I actually grew to love the extrasensory experience of morning watch standing (we won’t talk about how good we had it being in 5 section watches). The early hours spent on the water are like none other. The sun paints shades across the sea and sky and if you’re out on the bridgewing, your senses get served with added doses of wind and sea spray. That morning in Sweden was no different—except now the land grew closer, grew bigger around us. Soon a small boat came alongside and we waited for the pilot to climb aboard. Once present on the bridge, he stood out as the only person dressed in civilian attire. An older smiling man, he came centerline at the foremost point of the bridge, taking up station right next to me.

Unnecessary chatter is always minimized when the ship is in a Restricted Maneuvering situation. So we greeted each other without caring about first names or other ordinary world pleasantries and instead came up with an approach for moving through his home waters as a team. I soon forgot my nervousness and settled into the rhythm of the ship.

“Starboard ten,” the tall Swede leaned over and spoke to me in his soft and bouncing accent. We had reached a position where it was appropriate to turn.

“Right ten degrees rudder!” I responded loudly, my words nearly stepping on the end of his.

“Right ten degrees rudder aaaaye!” answered the Master Helmsman with an accent so southern that I never even knew it existed until I joined the Navy and moved to Norfolk. He was a cocky second class petty officer who took delight in mocking young ensigns who messed up delivering their standard commands. I knew this because I had stood behind him on many evolutions as the Helm Safety Officer, and he had told me as much.

In everyday life I am wholly opposed to yelling, but in my position as Conning Officer I wanted to ensure that my voice was responsive to the pilot, clearly understood by all, and hopefully confident-sounding. I also was fully aware that the Captain and Executive Officer were perched in their respective seats and incorporating me into their overall calculus. As one of the few voices permitted on the bridge, I wanted to be thought of as unremarkably reliable.

“See that house on the right?” the pilot said after the ship completed a turn and we steadied up onto a new course. I looked out to a house nestled near large rocks with clearly manicured landscaping. I nodded to the pilot.

“It belongs to one of the members of ABBA.” He looked at me with a grin.

I nodded with a smile, allowing myself a sliver of enjoyment for this free bit of tourism through Swedish waters. By this stage we were a few hours into the evolution. The ill feeling was long gone but I could now sense a growing wear and tear on my brain and body. I had been working hard to stay focused on our current course, speed—always ensuring that I correctly translate the pilot’s slightly different commands into our US Navy speak.

“You doing okay?” The Officer of the Deck, another southerner named Brian, looked me up and down. He was always easy going and with a wry sense of humor. I could read in his face that he knew I was tired. But I could also tell that he knew I was doing a good job, and that changing horses midstream in this evolution would not be the best for the overall bridge vibe. And I didn’t want to be relieved, no matter how tired I felt. I wanted to finish what I had started.

“Uh huh,” I told him, “I’m good.” We completed our non-verbal dialogue and then zoomed back out to the primary task. Between the kindness of the Swedish pilot and the quiet confidence I’d picked up from the sailors surrounding me, supporting me, I really started to feel something change. Like I’d started to belong.

“Restricted Maneuvering…Casualty Control Procedures…remain in effect.” This was the refrain heard by the Boatswain’s Mate of the Watch over the ship’s intercom until at last we reached our anchorage point. The Special Sea and Anchor detail was secured. We were done.

“Megan! Jonathan!” The Captain addressed me and the Navigator as he hopped off his chair to take leave of the bridge, “Hell of a job getting us in here.”

On the Norfolk waterfront our Captain was a fairly notorious man. An officer with a strong Louisiana lineage, he was smart, competent, loved his entire crew—but used the most colorful language of any commanding officer I would ever know. He also was not one to give out compliments unless you really earned it. With his acknowledgement of my morning’s endurance, I smiled to myself and removed the binoculars from my neck.

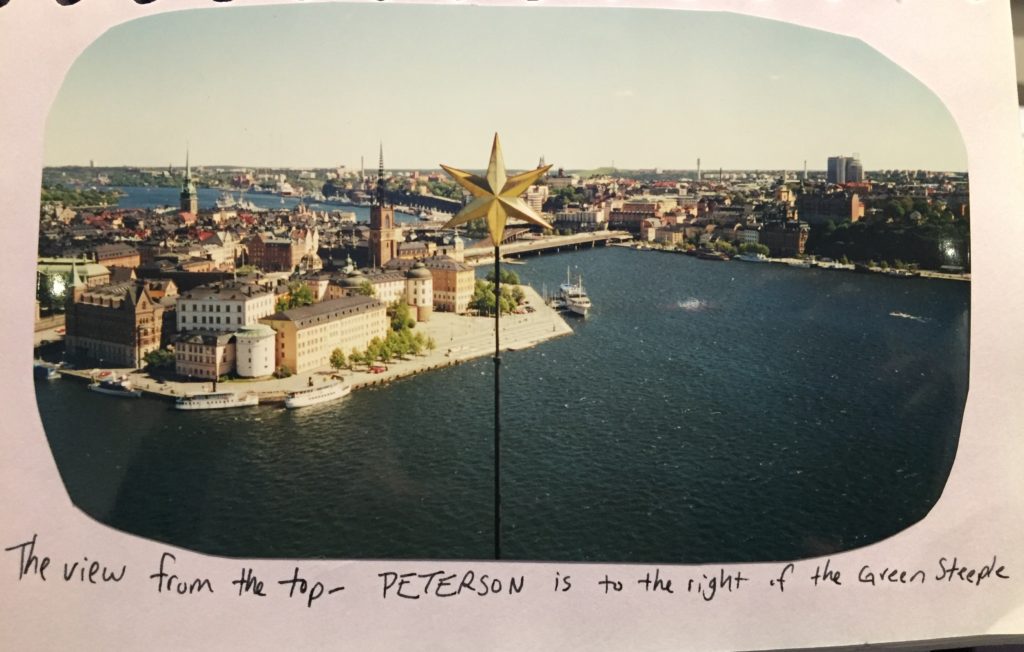

That entire experience was 19 years ago this month. I am thinking about this now as I find myself back in Stockholm for the first time since making that port call. I am also reflecting on the experience because also in this week I received the last set of orders that the Navy will ever give me. The orders allowing me to retire.

In many ways, I find it strangely fitting to be granted retirement while focused on a different sort of Navy trip back to Sweden. For one, I feel as though the orders mark a sense of accomplishment—the same accomplishment of endurance that I first felt as Conning Officer pulling into Stockholm. Over the years, the military has been kind enough to bestow upon me numerous end of tour medals—but honestly, most of them don’t feel as richly earned as those victories I scored in the earliest days.

Now, after 20 years, I’m happy to say that I’ve not only managed to outgrow that terrible ensign’s haircut, but I’ve also managed to learn a thing or two about being a sailor. I’ve learned a lot about how reliance on teamwork and having some faith in yourself are two big things that help propel you forward. I can’t believe that it’s been almost 20 years since I first went to Sweden. It’s a wild experience to reflect upon.

I can’t say exactly what’s ahead for me after the Navy, but thanks to those memories first carved in the waters of the Baltic, I am no longer as worried as I used to be as a 22-year-old. I’ve got enough experience under me to suspect that I’ll probably be okay. And even if it’s super hard, these past two decades have taught me that I really can count on the support of others when I find myself approaching waters where I don’t feel so confident. I have no regrets about leaving the Navy—but I know that I will miss many of its best moments.

Sweden, like naval service, has offered itself up as surprising navigation aid for me in this chapter of life. I’ve still got a little bit of time yet to serve, but much like that first big foray on the bridge, I will never forget that I left Stockholm once again feeling a bit more steady about things and with a positive sense for where I’m going.