“You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot keep spring from coming.”

-Pablo Neruda

The other day I was riding the #44 bus in Dublin. It’s a local but far-reaching route, the kind you find most almost anywhere in a capital city. We pulled away from Pearse Street and snaked southward and into Dublin’s environs. As we went, I watched with familiarity as people boarded with increased frequency as the landscape changed from urban scrabble to a green-soaked countryside. When we stopped in Dundrum, an older woman came aboard and took the empty seat just next to me. There were still about 20 stops to go before I’d finally get to Enniskerry.

The afternoon was a sunny one with liberal patches of blue interrupting the cloud layer. These spring days still feel like a novelty, and I kept my eyes trained on the world in renewed captivation. As the bus inched from one stop to the next, soon we passed a church with a hearse parked just outside. The woman seated next to me and I, we both instinctively crossed ourselves—just as I know that others on board did the same. For me it’s a reflex that I picked up from living in this country, and it’s something that I continue to do without giving it a second thought. Except on this particular occasion, I do.

Just a few days ago, my mother and her sister lost their father. He was the anchor of all things in their world and as such served as the last tether in their particular family history. Here in Ireland, I have no idea who is reposing in that hearse, but I do know that in a few days’ time I will be attending to my own service of remembrance.

It’s a strange and complex emotion, the experience of grief. And honestly, since I’m so far removed from the minutiae of my grandfather’s departure, I won’t truly process it until I fly home and cross the line into the Pine Tree State.

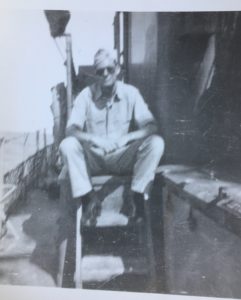

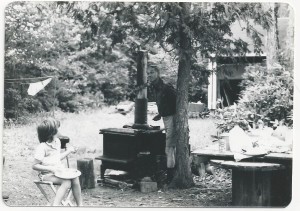

My grandfather was just the type of person you’d want to have. He’s the type of guy whose daily activities would have served as fodder for a Robert Frost poem. He didn’t have the sharp edge that is resident in those of us raised in southern New England. Instead, his inclination was to just get on with things. He found satisfaction in the execution of his unassuming activities—regardless of whether it was fishing on East Grand Lake or chopping wood for the long Maine winter. I only saw him grow cross once when we were at camp one summer afternoon. After tossing around a beach ball, an errant throw set it gently upon the massive that reached to Canada. The summer wind quickly blew it away and beyond our swimmable reach. He saw what we had done, the ball now shrinking in size, and he offered a short and baffled commentary before hopping into his red wooden boat to go out and retrieve it.

Now back in Dublin, I think about all of the things that have followed in my life since those far away memories in Maine. My grandfather had no history or traceable connection to Ireland, but I still think of him as I wander the places that give me comfort. During this visit I unexpectedly signed up for a guided tour of a graveyard just beyond Dublin’s center. Its dates back to the 7thcentury and bears the unusual name of Bully’s Acre. Inside the cemetery’s walls are sections set aside for military men: officers and noncommissioned officers. There are those who fell during the 1916 Rising. Millions are claimed to be piled inside this space, with most now forgotten with headstones never created or now broken beyond repair.

During our graveyard walk I thought about my grandfather. I thought about where he might finally come to rest, and how he might be remembered. I think about all of his life’s work.

I’m enough of a realist to understand that ultimately, we all crumble away and coalesce back into a some common collective like the one found at Bully’s Acre. But at the same time, I believe that there is something to be said for the energy that we generate and pass on to our descendants. It’s not about my grandfather’s newly-branded “heirlooms” that will be carted away from his now empty house. Nor is it even about preserving his hard-won campaign medals of war and that signified one person’s sacrifice for a flag. These things, of course, have value to those of us who share an immediate connection to him—but these things too can’t last.

If we’re lucky, I might wind up leaving behind some broken down stub of a grave marker that may or may not be visited on a sunny spring day by some anonymous visitor. But even if no one ever knows who I am, or who my grandfather was, or what any of us ever did, I still believe that there is value in paying respects through ritual or silent contemplation. And I of course will feel something a bit more like textbook grief once I finally do get home. Once I set foot inside that Episcopalian church up in Augusta, the one I was last in when we said goodbye to my cousin, I know there will be sorrow. But for now, I am thinking about all of the things that came before, and I do it with a smile in my mind. I invoke my grandfather’s smile, and for me this is everlasting. I see it in his great grandchildren, and if we manage to carry on this one thing forward, it will have been more than enough for everything that he gave in this life.