Anyone traveling through Ireland’s orbit knows that 2016 will be special. This marks the 100-year anniversary of the Easter Rising—a blow on a faltering wall that ultimately brought the end of British rule over the 26 countries that now comprise the Republic. At least that’s how I attempt to describe it within the space of a single sentence.

With an entire year of remembrances planned, I imagine that there will be 52 editions of the Sunday Times jam packed with expositions, reviews, tutorials, and general food for thought on the subject of the Rising. It’s an important commemoration for the Irish, and although a bit of an outsider, I felt compelled to visit Dublin this past weekend and learn a bit more on what it was all about.

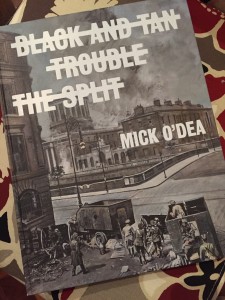

Last month I wrote about an unforgettable Christmas dinner with the Irish Army spent down in Kilkenny. Among the esteemed guests were three artists of note, Blaise Smith, James Hanley and Mick O’Dea. I happened to be seated next to Mick, and as we chatted about all sorts of things he mentioned an exhibition that he was feverishly working to complete that was set to open after the New Year. From his enthusiasm I knew at once that I’d love to come and see it.

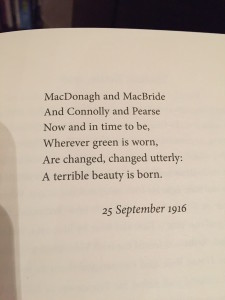

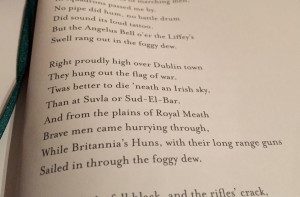

Through the buzzy atmosphere of the Christmas dinner, Mick had reminded me of lines from a traditional song that told the story of the Easter Rising. From that song, his exhibit emerged under the fitting title of The Foggy Dew.

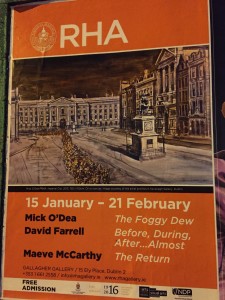

Mick is the current president of the Royal Hibernian Academy (or RHA in shorthand), a near 200-year-old artist institution located just off St Stephen’s Green in Dublin. Already claiming a body of work that includes landscapes, portraiture and historical captures (to name only a few), The Foggy Dew was a synchronous cultivation of approximately two decades of study, contemplation and general marinating—and it all culminated at Mick’s current posting just as Ireland would be looking back on a centenary of proud and sometimes volatile history.

As an Irish-American who studied a bit of Ireland’s politics and history while in college, I had some idea of what I’d see when we arrived on that cold and quiet Saturday morning. It was myself, a friend in the Irish Army, and his lovely partner whose parents were Irish, but she was born in London before moving back home as a young girl. It didn’t strike me at the time, but in some small way the three of us represented strands of the great Irish web that counts the Easter Rising as its nexus.

Mick, the artist himself, was good enough to meet for breakfast before walking us across town through Iveagh Gardens, around the perimeter of St. Stephen’s Green and into the RHA on Ely Place. On this morning as the streets slowly warmed and snow could be recorded on the Dublin Mountains, we had the run of the place as the city lay dormant and still bogged down in Friday night. A most fortuitous turn for us as we stationed ourselves at the exhibit’s starting point with Mick serving as our personal tour guide.

Whatever Ireland’s schools are doing to bring their students closer to 1916, they really must start right here.

On the entrance wall Mick had mounted the portraits of 18 personages with connections to the 1916 Rising—and just off to the left could be found two additional portraits. Mick, so much more than a mere artist, quickly proved to be a de facto curator for his country as he recounted the biography of each face. Some stories, like that of Éamon de Valera, were easily recalled, while others like the actor John Loder had surprising connections to both the Easter Rising as well as the Hollywood film industry. It was clear that Mick has spent his life building a treasury of historical footnotes in his mind, and the fruits of his scholarship was now looking back at us in the RHA.

-

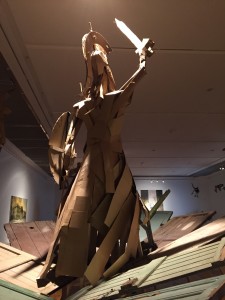

After bringing us through his deck of portraits, Mick took us upstairs to the main viewing salon. As we crossed the threshold, we noted that the room was anchored on each side by an immense canvas. Within the space, sculptures constructed from cardboard occupied various positions of frozen surprise: perhaps soldiers or rebels suspended in air, captured in the immediate aftermath of being blasted. Nelson’s Pillar and a 1916 monument from Mick’s hometown of Ennis were also constructed from cardboard and on display.

Daniel O’Connell the famous liberator and these days the guardian statue anchoring the eponymous Dublin street stood just off the entryway in larger than life form. He was even capped by the usual Liffey seagull.

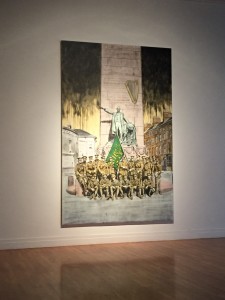

I’d really love to bring you through each station as Mick showed us around, and to be fair you need to know a bit about Dublin’s geography and the 1916 history in order to appreciate the layout. But I don’t profess to know a ton, nor do I imagine that this blog will capture Mick’s comments with complete accuracy– but I did know enough to appreciate what he was aiming to achieve. The Foggy Dew was like a walk through time and space. On one of the 13×9 foot paintings called “Imperial City”, soldiers march past Trinity College (on Dublin’s South Side). This canvas sits behind a sculpture of the Helga, the British gunship that sailed down the Liffey and shelled Liberty Hall during the Rising. As we continue across the room we find ourselves on Dublin’s North Side.

Mick painted this from an old photo and extended it upward to include more of the obelisk, Parnell, and the inscription that makes up this monument on the city’s North Side.

Mick positioned his painting of British soldiers posing with the upside-down captured rebel flag (now hung on a bayonet instead of the GPO) directly opposite of his “Imperial City” piece. Walking towards the middle of the room you’ve got the cardboard sculpture of Daniel O’Connell, just as he sits on the edge of the Liffey and keeps each side of the city in its rightful place.

Mick explaining to a visitor how the “gunship” is constructed from old doors salvaged from the hospital next door to the RHA.

After we finished touring the exhibit, Mick brought us into his studio to provide an understanding of his preparatory process. In order to construct the men now suspended from the ceiling, he found tiny plastic World War I army men (for lack of a better term), carefully sliced off their Brodie helmets, and then constructed small cardboard likenesses like the one you see above. From there he blew up the scale to something more lifelike.

The four large paintings, when taken with the accompanying 20 portraits really struck me as something of a national treasure. Mick, by the way did this entire project over the course of a single year. To achieve so much in such a short space of time seems utterly inconceivable.

I’m not Irish, and I know that the 2016 commemorations have only just begun, but it would seem to me that long after the cardboard sculptures must come down and be destroyed, it is the body of Mick’s painted work that should be preserved as a whole. I simply can’t see the individual portraits split up and farmed out to homes and museums flung far and wide. Taken together they tell a powerful story of a country that had an inexorable plan for itself. Mick has done an extraordinary job of bringing the past alive, and while there must be precious little surviving from the actual events of 1916, these paintings make the case for something that comes pretty darn close.

The day that we left the RHA, the Irish Lotto was boasting a €7 million jackpot to the person who came up with the right numbers. Nobody won, and indeed the three of us had half considered playing, just so we’d have the money to scoop up Mick’s work and ensure that it would be preserved as a whole somewhere. Option B, we decided, was to find an individual with an appreciation for what exists in The Foggy Dew. Any rich benefactors out there? Perhaps one sporting a Claddagh ring over in America?

I have no idea where these paintings are going to go once this run is over, but there is no doubt in my mind that this artist has done his country and heritage proud by what he’s accomplished. Mick, if you’re reading this, thanks very much for sharing a bit of your time and talent with us.