In some corners more than others, it’s easy to peel back the edifices of right now and gain a view into what came before. Rome is an example of this all day long. You see it in construction sites put on pause, the large and small digs that they’ve dug now exposing a world that nobody imagined was there when they first set upon building whatever it was they were doing.

It’s well known and that when building first building Rome’s metropolitan, they kept coming upon so many archaeological finds that each stop resulted in a delay in production timeline. And then there are the more cynical (or perhaps realistic) Romans who will tell you that at certain points, the work didn’t stop. Stuff was found but they just kept blasting through whatever was there. I have no idea if this is true, but it’s understandable enough given the struggle between preserving a gone-forever past and improving upon a crumbling foundation that is no longer fit for modern society.

Last weekend I went to visit a 2014 discovery that was ultimately restored even as though life continued on just above. It’s a fairly and unassuming place called La Scatola archeologica- the archeological box. It was uncovered while applying earthquake-proof safeties to a 1950s building located out by Circo Massimo. This spring the number of visitors who can now go and see it was increased, but the hours are still neither plentiful nor even convenient. With so many sights to trip over in Rome, it is understandable that supply and demand without sufficient support to show it all off continues to be a challenge.

If anybody knows anything about Circo Massimo, then they might think of the following: the Circus itself, the United Nations, or the Knights of Malta keyhole located near the Orange Garden on the Aventine Hill. The Scatola, however, is located not too far away and is also a part of the Aventine Hill. Unlike all everything else that I just mentioned however, you’d never know it was there.

There are loads of places in the world where you are shown spot that looks more or less unremarkable, except for the fact that there is a plaque or sign. On this day, this happened in this spot. You squint your eyes and try to take it in. Unless you have a vivid imagination, this can be hard to do. The flip side is a visit to a museum, where many artifacts are placed behind glass and accompanied by a short description about where it came from. This too, is often the best we can do to provide an understanding of the past. And then flip side of both of these experiences is to catch the past as it somehow endures to coexist within the pounding city. I’m talking about a gas station down the street from Circo Massimo that sits at one of Rome’s not-quite-intersections/not-quite-jug handle turnaround points that for good measure also has a tramline running through it.

When I went to visit the archeologic box, I at first had a difficult time figuring out exactly where it was. The website doesn’t give much details about the address, and of course there aren’t any signs. Just a gas station and some trees and then a big building that is either an office or residence…or likely both. In any case I walked back and forth in front of where I thought I was supposed to be until a nice man with a lanyard took interest in my puzzled state.

As promised, the tour was small and the man only had a printed piece of paper in his back pocket with my name on a reservation list. He brought us in and asked us to be quiet, as this was a workplace. Indeed, we passed through modern glass doors and a receptionist before being brought down a level. Nothing about the journey, save for a few framed photos of mosaics hanging in the lobby gave hint to what we were about to see.

Down the marble stairs, we were finally brought to a door that had a single standing advertisement. As our guide unlocked the door, we immediately stepped inside a place that existed 2000 years ago. Back when the street level was below our street.

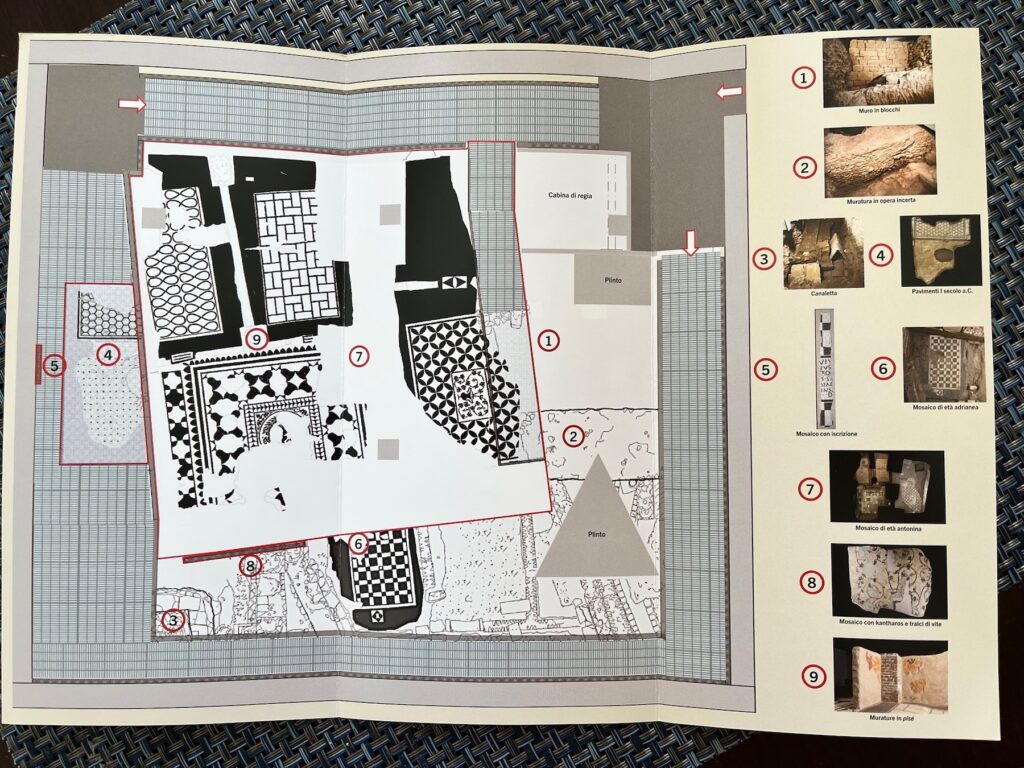

The interesting thing about this tour of yet another domus in Rome, was that they had set up a sort of light show to fill in the holes (or breaks in the mosaic floors or walls), to give us a virtual understanding for not only what was found here, but how it probably looked. The level detail (and indeed the detective work of the archeologists) gave an impressive look into how life probably was back then. Museums and empty fields have value, but the fact that we were standing underneath a massive building on a street that I had traveled many times without thought made 2,000 years ago feel very familiar.

The flip side of this wonder of course is that you, as a modern citizen, must learn to coexist and appreciate the old with the new. Perhaps because I spend so much time driving in a place like Rome, I get to come into contact with this sentiment more often than not. In Rome and other partially-preserved cities like Boston (yes, I said it), it is easier to partake in a slice of what once was without feeling like you’re in a sterile museum environment. Quaint and tiny streets gain you access to an old world that Is not suspended on a protective backing and behind glass. Those are also the roads that you will find nearly impossible to negotiate. It’s easy to start cursing up a storm about this until you take another trip back in time and remember that all of this is a mess for a very important reason. These places hold the keys to a past that we don’t get to see that often.

I am fairly confident that I excel only at scowling over the more inconvenient parts of the city, the many times where I come upon the World’s Most Ridiculous Diversion and suddenly find myself heading in the opposite direction of where I want to go. I deal with this all the time. For me at least, there is a lot of inherent stress that comes with living in an overcrowded and culture-saturated city. That’s not a criticism of Rome, but more of a criticism of myself and the tendency to get lost inside my own mind. This is why I so appreciate the softer moments. The anonymous stopping points hidden just below the surface and humbly call themselves an archaeological box. More than anything else, these are spaces that are worthy of their space and make everything else going on in the present day well worth navigating.