Without a doubt my favorite class in high school was photography. I loved it not because we were given hall passes to wander the school for an entire period—but rather, because this was in the early 90s and we were walking about with old timey SLR cameras. With generous spools of film turned out by our teacher, Mr. Wight-Waltman, and a spacious dark room in which to work, it felt like one big canvas in which we could draw out our inner personalities.

My love for being a darkroom rat started early. I remember my father transforming the downstairs bathroom into a makeshift darkroom, the images coming into view as they crawled across big sheets of photo paper under the red light. Thinking about that tiny bathroom now, I wonder where he found enough room to lay out all of the trays.

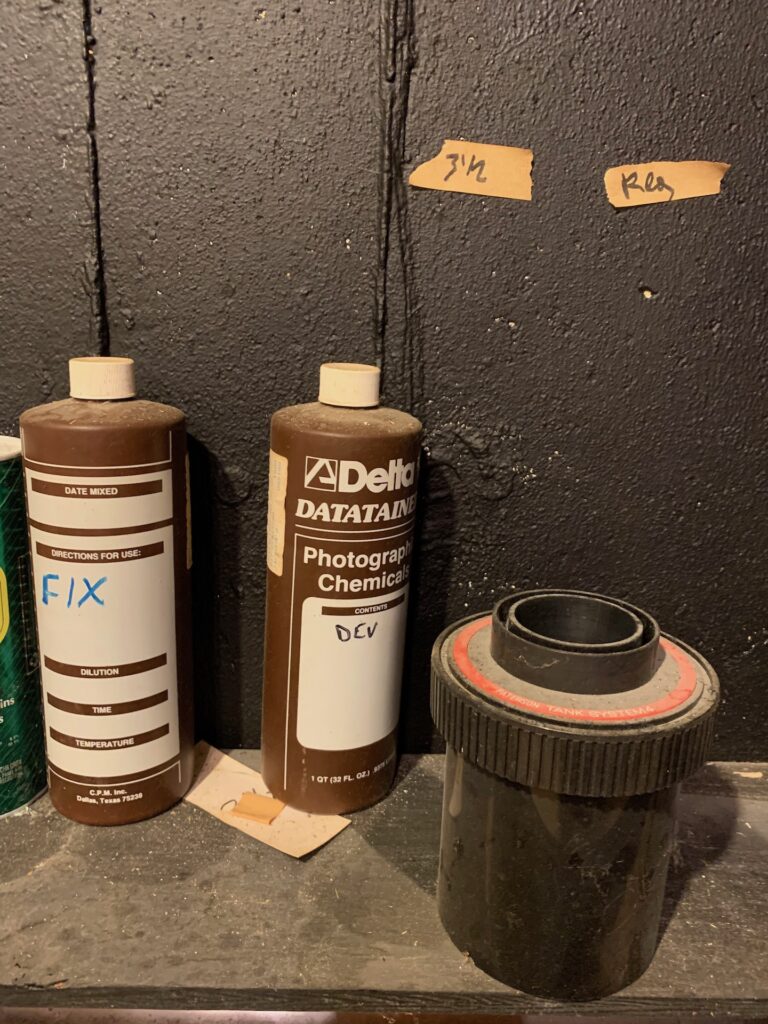

It wasn’t until my senior year that we would transform a corner of my father’s cellar into a dedicated darkroom. All those years later, he still had his old Omega enlarger, so it felt as though the remaining acquisitions would be easily accomplished. Ortins Photo Supply on Main Street stocked us up on used equipment that had us off and running: a photo timer, the grain finder, the developing tanks…and of course, Ilford paper and Kodak T-Max and Tri-X film.

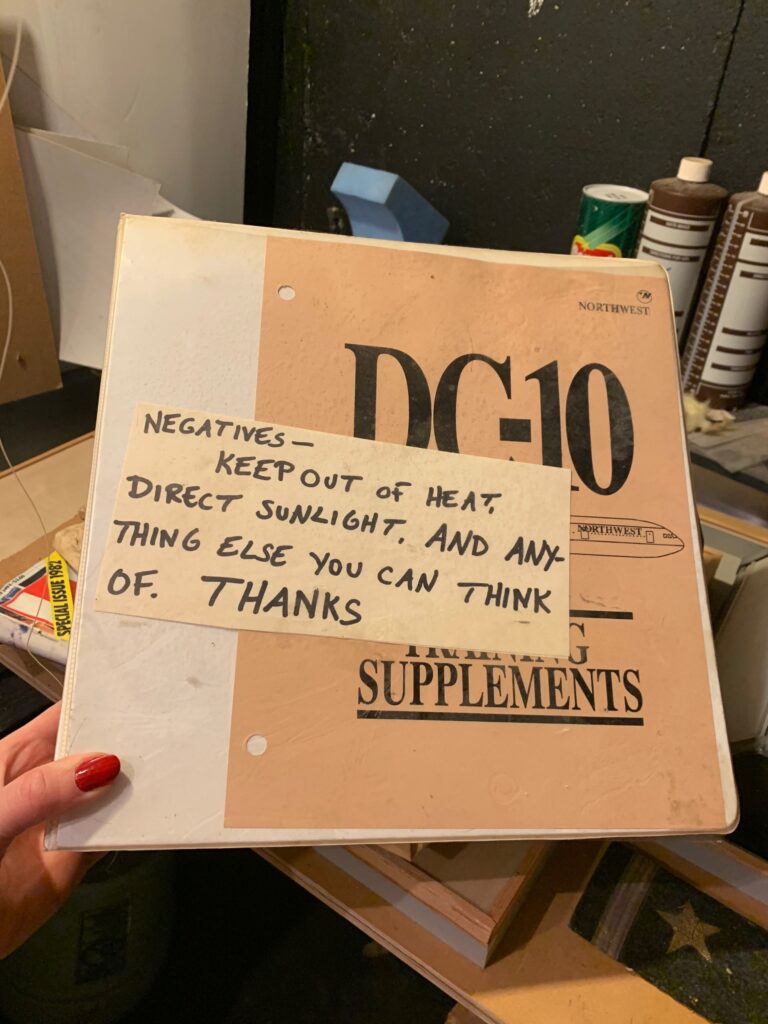

In the land before digital cameras and storage clouds that encouraged reckless photo snapping, we thought of photography in a fundamentally different way. Each frame in a roll of negatives was to be considered carefully; you didn’t want to run out of film when you suddenly found yourself in a groove. Worse was the beautiful yet half-exposed frame that came with a surprising end of roll. Further, the manipulation undertaken to perfect each enlargement was something far methodical and painstaking than what you get with a smartphone app. Kids these days.

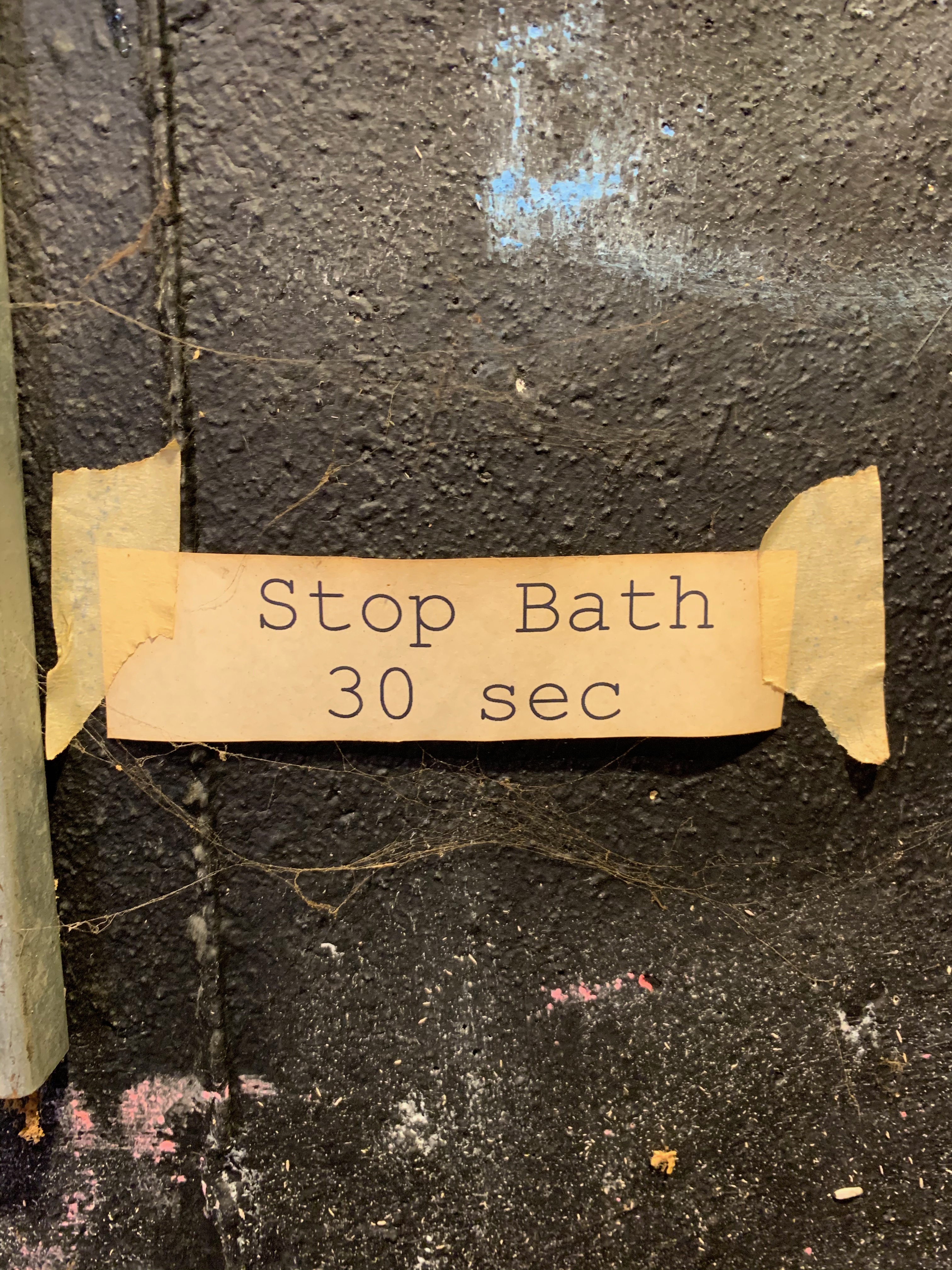

I never rose to the exalted ranks of a technically accomplished black and white photographer. Instead, I took great pleasure in the going through the steps that came with agitating a black canister of developing film—hoping that I got the temperature and proportion of water to developer correct. I loved unwheeling the wet film from the spool to get a sneak peek at what awaited before clipping it up on a makeshift clothesline just beyond the tub marked “Perma Wash”.

The other great thing about the darkroom is that it mandates a civility that you don’t really get anywhere else in a house of activity (although, always remembering to lock the bathroom was standard growing up). When the red pilot light was on, a person at the top of the stairs could look down in to the cellar and know that someone was working away inside. Opening the door to daylight was like treason when it came to protecting the sensitives of photopaper. I also loved the pitch-black performance necessitated by cracking open a canister of undeveloped film and easing it on to the spool. There was something peaceful and meditative about all of this.

Once the negatives where dried and cut into strips, the real fun began by making a contact sheet of one’s work. With that in hand, you could get a better idea of which images seemed to turn out the best—and which ones would likely be unworthy of enlargement. Black and white photography is a multi-day endeavor that takes a great deal of trial and error. You know this going into it- and if it is something that you really can latch on to, you understand right away that the process is just as enjoyable as gazing at a well-finished enlargement.

I took my love of photography into college with me. While at Trinity, I joined the Photography Society just so I photograph Dublin and then use their darkroom. I even gave some basic lessons to new joiners who wanted to learn about developing film. Dublin in the 90s—much like Falmouth High School—offered a world of texture and grit that I never grew tired of capturing.

All of these memories are now twenty years old. I can tell you this now because while home, my brother and I took stock of the darkroom’s existence and decided to make some major renovations. It wasn’t because we were no longer enamored with black and white photography. Unfortunately, it was more because time, technology and our personal schedules had marched on. What we were still referring to as the darkroom had become nothing more than a glorified storage room overrun by cobwebs and mystery insects. The enlarger was hidden under piles of boxes. The developing trays and any remaining photo paper were lost in a sea of just about anything else you could think of.

The plywood separation wall that my father once installed cellar came down more quickly than it had come up. I remember painting the interior a flat black to really bring the new space to life. Inside and out, we had put in some smart aleck-y graffiti on the walls and instead of a normal door, we repurposed a “Welcome President [H.W] Bush” sign that had been posted at the Mashpee rotary the year that he visited back in 1990. Don’t ask how the sign fell into our family’s possession, but it made for a perfectly-sized door.

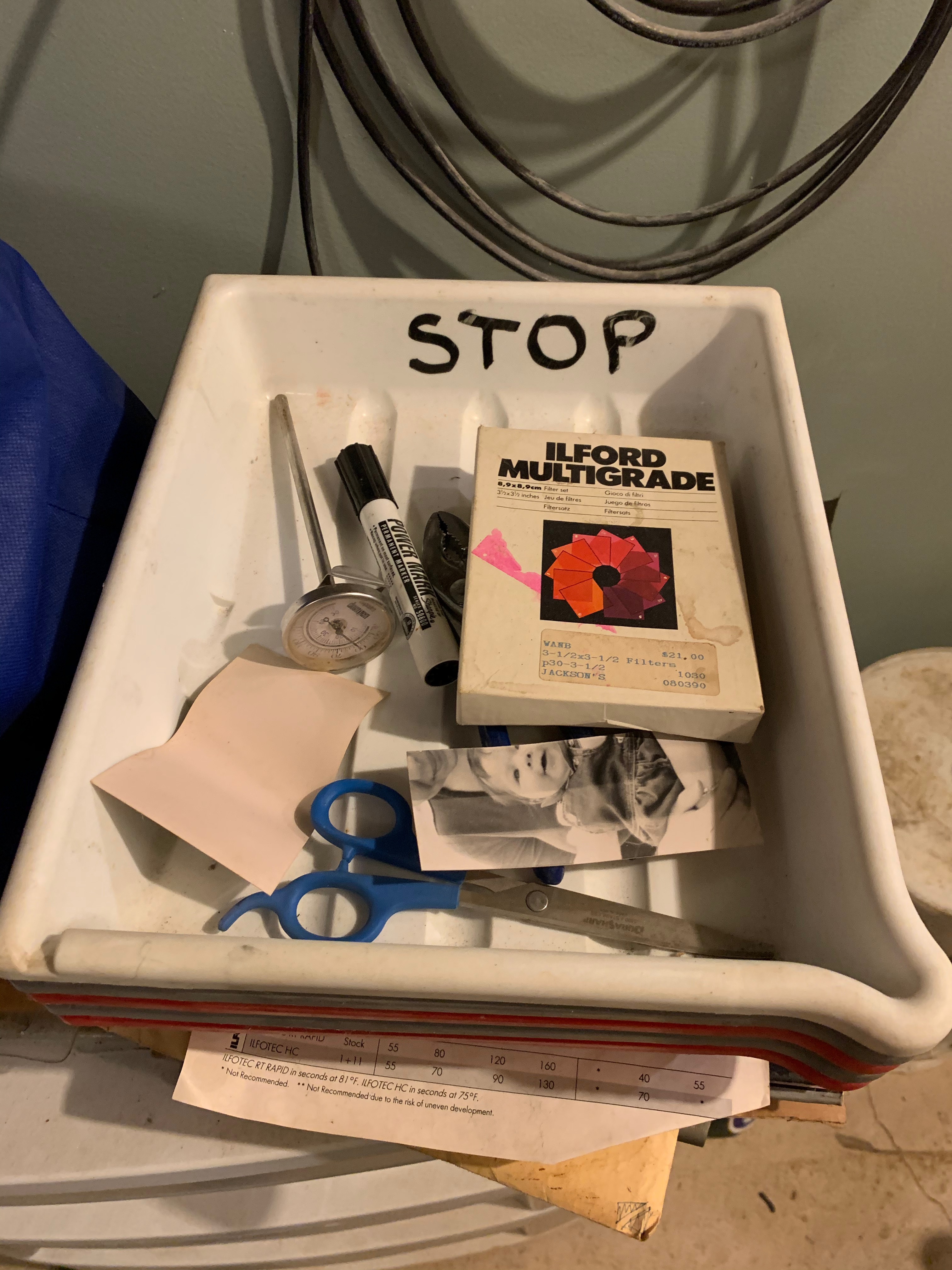

Once the wall came down, my brother dismantled the stainless-steel sink and long plywood countertop. As for me, I tried not to get stuck in the nostalgic quicksand while removing the bits and pieces of the dusty equipment. Old test strips, squeegees, a stack of photos that I once took on Dublin’s Windmill Lane. It was tacitly understood that we would not be getting rid of this equipment—all of it now seemed like a lost art that would surely find new life again one day. If not by us, then perhaps a younger generation who could marvel in the process of bringing life to life on a big white sheet of paper.

So, rather than lingering too much on the collection of expensive light bulbs, unopened photo paper, and the unmistakable scent of photo developer now soaked into the plywood, I hauled out my smartphone and quickly framed some memories.

It seems a bit crass to think that I used a handheld piece of rapid computing to capture the workhouses of traditional photographic production. Everything these days is accomplished at lightning speed—my trusty packet of photo filters was a relic that would know the first thing about facetuning. You want physical copies of photos in hand? You now open up your laptop or head down to CVS and dictate how large you want them. They can hardly make for you a cool-looking photo-negative enlargement, but the result of modern technology is that everything is now done with a speed and quality that we now take for granted.

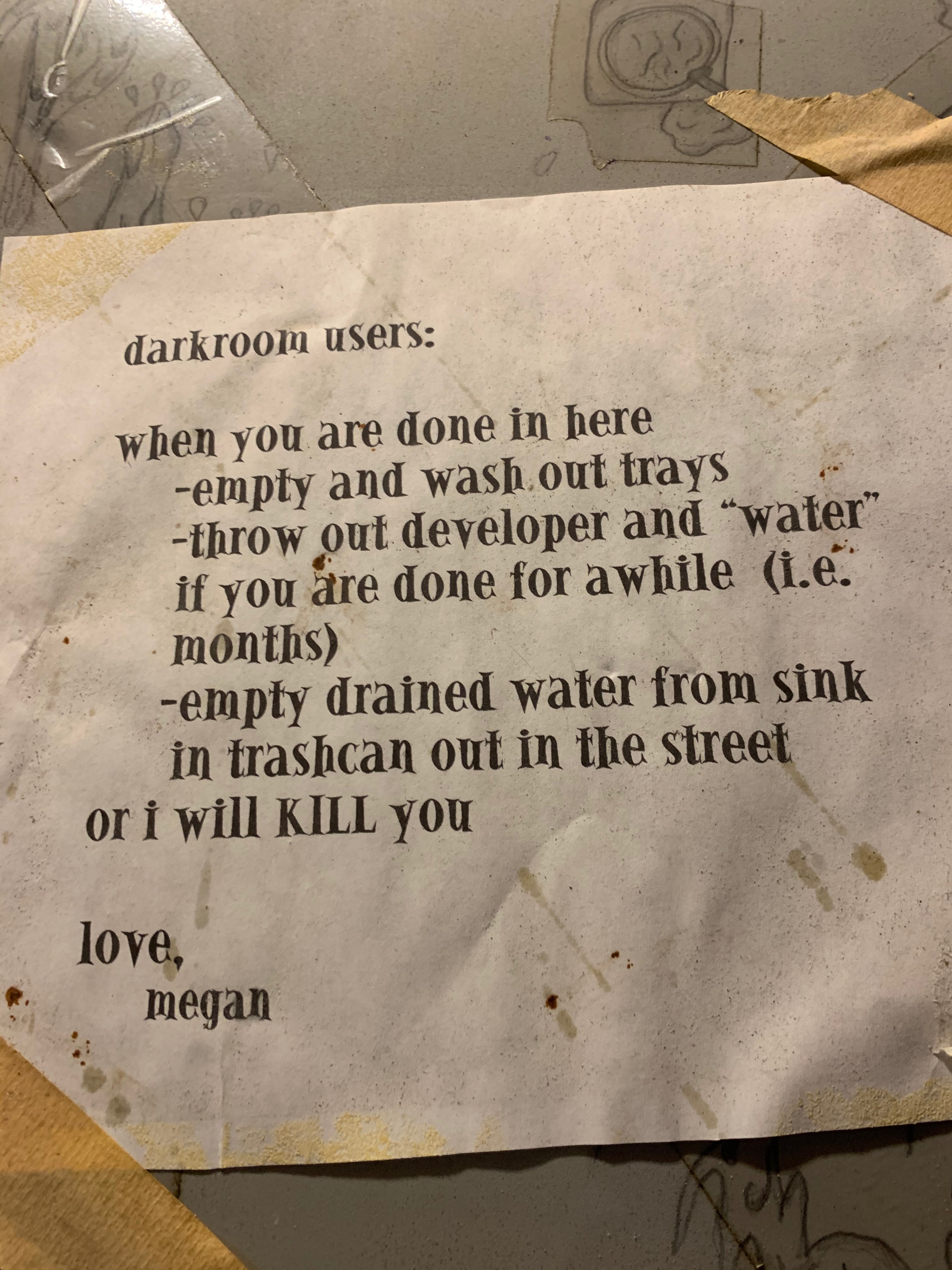

I haven’t even mentioned that we no longer have to wonder where we should dispose of that used developer fluid.

The old darkroom will now be repurposed into a room for an air compressor, a TRX, and maybe some other storage needs that now rule the day Non-high schooler Megan recognizes that we the bandwidth to support a functioning darkroom just isn’t there anymore. But still, through this collection of hastily-framed photos, I wanted to retain some visual memories of that time spent down cellar. My memory fades and so I went an easily-retrievable tap to remind me of how each tool felt, how the timer sounded. How I used to reach up overhead onto the wooden beam without looking to flip on the red light. The new dull brightness somehow effecting a shift in my entire rhythm.

I miss the simplicity of those days, but in dismantling the darkroom my brother and I both knew that it was the right thing to be doing. It didn’t mean that we were disrespecting or discarding our carefully-learned photo skills—it just meant that we had to acknowledge the forward progress of time.

Even if we do finally give away our collection of darkroom equipment, I will not be too disappointed. I’m grateful to have grown up armed with these simple tools. An old Canon AE-1 and a modest little production room that to me, opened my eyes up to things I never would have seen otherwise.